We have been living in the digital information age -- the age of the Internet, for some time now. For most people, the World Wide Web or simply the Web, is a norm in their daily lives at work, in business and in personal communications.

Most businesses or companies today already own a “Web presence" i.e. they have developed and published a Web site about their business or company. Such Web sites are regularly maintained or updated with the latest information, for e.g. a public listed company may publish their latest audited or unaudited financial results on their Web site such as Petroliam Nasional Bhd (PETRONAS).

As time passes, we tend to take all these online materials or information for granted. Well, it is there posted up for the public, for the world to see and read. So, what is wrong with copying the information wholesale or portions of it as it is?

All the online materials we see, read or come across are created with copyright laws in mind. Can any person just “copy and paste” from materials published online (or from printed media) belonging to other people without authorisation or the owners’ consent or even a citation or acknowledgement?

As an example, for a business or company or an individual who wishes to develop, publish and maintain a Web site, two major copyright issues exist:

- To protect all the contents, materials (e.g. audio and video tracks, images and pictures) and links of its Web site from copyright infringement; and

- To ensure that all or any of the contents, materials and links used or reference to in its Web pages are not infringing on another owner’s copyright

Copyright law is a branch of intellectual property law along with trademarks, patents and industrial designs. I will discuss the protection and rights provided for by copyright laws in general, with references to Malaysia’s copyright law -- the Copyright Act 1987 and the Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997, amendments made to update the Act in relation to online content and materials.

II. Copyright Laws and Copyright Protection

1.0 What is copyright protection?

Copyright laws provide protection to authors of “original works” against unauthorised use, duplication, reproduction, alteration, transmission, distribution and passing off as another’s original work.

If copyright is infringed, the copyright law provides for legal remedies and restitution against the copyright infringer or offender.

2.0 What can be copyright protected?

“Original works” in material form of qualified authors are copyright protected. This means that in order for a work to enjoy copyright protection, it needs to meet certain eligibility criteria:- It is an original work -- The nature of originality in copyright laws does not mean that the work must be an expression of original ideas, but rather the expression of thought not copied from another source

- The work must be written down, recorded or otherwise reduced to material form

- The author is a qualified person -- Since laws involve jurisdictions, a “qualified person” can be generally defined as a person recognized by the copyright law jurisdiction. For e.g., in Malaysia’s copyright laws, a qualified person is defined as:

“(a) In relation to an individual, means a person who is a citizen of, or a permanent resident in, Malaysia; and

(b) In relation to a body corporate, means a body corporate established in Malaysia and constituted or vested with legal personality under the laws of Malaysia.”

- Literary works

- Musical works

- Artistic works

- Films

- Sound recordings

- Broadcasts

- Published editions

- Derivative works e.g. typographical translation, adaptation or arrangement of works eligible for copyright

- Collection of works eligible for copyright, but must be selected and arranged in such a way that the resulting work becomes an original intellectual creation

There is no real difference between traditional copyright and electronic copyright. The distinction lies in the way the electronic or online material has to be decoded or read and used by the user.

Works that are published or transmitted in electronic format or medium e.g. CD-ROMs, Web pages of Web sites or portals, online databases, computer programs or software, etc are copyright protected as their printed or traditional medium equivalents.

Online materials can generally be categorized into three major groups:

3.1 Electronic information

Electronic information is information that has been converted into electronic form for the purposes of transmission, decoding and manipulation, storage, publishing and displaying on or from digital media or in cyberspace, mainly via Web browsers and computer programs in tangible and specific form or function.

Therefore, the contents and multimedia materials we see and read on all Web pages, Web sites or portals are copyrightable materials. Reports, charts, graphs, and other data attached to electronic mails and easily sent across cyberspace from one party to another may be copyright materials, and copyright may be violated.

The computer industry’s most famous copyright infringement case is the Napster case of downloading and sharing copyright music files in digital form.

In RIAA v. Napster, Inc., it was held that Napster did not copy or distribute the digital music files, but the users who were allegedly committing the direct infringement by downloading, copying and sharing the digital music files. [Ryan, 2002, p. 495]

However, Napster was found guilty of both contributory and vicarious infringement. The plaintiffs claimed that Napster’s facilitation of the identifying and downloading of the files constituted contributory infringement.

The plaintiffs also claimed that Napster had the ability to control the activity by allowing or filtering out the files, and had also gained financially from advertising revenue based upon the number of “hits” or “visits”, which constituted vicarious infringement.

3.2 Computer programs and computer software

Copyright treats computer programs or software as a literary work. Actually a software product can be distinguished from the computer program since a software product may be made up of different copyright works.

For e.g., a software product usually consists of:

- A designed packaging box

- A printed user guide or manual

- Diagrams, graphs, charts, artwork, screen displays, images in the user guide or manual

- Sounds and sound recordings

- Video and animation; and

- The encrypted or compiled computer codes that makes up the computer program, stored in a CD-ROM or floppy disk

The creator of the computer program i.e. the programmer is recognized as the owner of the work unless the programmer is an employee and created the program as part of the job responsibility, in which case the copyright of the program automatically belongs to the employer, or the programmer has assigned the copyright to another party.

Copyright protection is extended to the computer codes written in a computer language as a literary work. Hence, copying in part or in whole is not permitted without the copyright owner’s consent. If another programmer is able to reverse engineer the computer codes of a computer program to study or examine the method of operation of the concept, and later independently write new computer codes to perform similar operations, then there is no copyright infringement.

This has led to several countries e.g. the United States and Japan, extending patent protection in addition to copyright protection for computer programs. Patent protection additionally provides the owner an exclusive right to make, use and sell the invention for a statutory period of time.

In Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 185 (1981), the United States Supreme Court granted patent protection to the computer program that contained a mathematical algorithm as a step in process. It was held that the computer program was patentable because it was not merely a procedure for solving a mathematical formula. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 115]

3.3 Databases

A database is a collection of independent works, data or other materials that are arranged in a systematic or methodical way and individually accessible by electronic, digital or other means to provide meaningful or valuable information. For e.g. telephone and street directories, customer mailing lists, photographs, customer credit card information, bill of materials, inventory data.

Advances in information and communication technologies have increased the use and value of databases enormously and highlighted the need for high security and the importance of protecting databases from unauthorized access, usage, copying and manipulation or modification.

Copyright exist in databases as literary works by virtue of the selection and arrangement in the compilation of the data.

4.0 Exclusive rights of copyright owners

Copyright owners have the following exclusive rights over their copyrighted works. These exclusive rights enable the copyright owners to exercise legal authority to control the use of their copyrighted works by others.

4.1 Reproduction right

Is the right to copy, duplicate, transcribe or imitate the copyrighted work in fixed form. In MAI Systems Corp. v. Peak Computer, Inc., 1991 F.2d. 511 (9th Cir. 1993), it was held that computer software downloaded into a computer’s RAM memory by the defendant to be used to diagnose computer problems was sufficiently permanent and fixed to have infringed on copyright. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 91]

Unauthorised scanning of any copyrighted work into a digital file and then using it on a Web site constitutes copyright infringement.

Two other technology issues exist which relates to reproduction i.e. framing and caching. Framing, which allows a Web site visitor “to view the framed site while the site owner’s proprietary material is displayed next to linked third party material in the same window” may constitute copyright infringement.

Caching is the technology used to copy a part of or all of the contents of a Web page for indefinite storage to facilitate quick access to the Web page in future. This is known as “proxy caching”, and tantamount to copyright infringement because the copyright owner’s right to reproduce is exercised. Hence, the copyright owner’s consent is required.

4.2 Modification right or derivative works right

Is the right to modify copyrighted work to create new work. Most Web site designers or developers tend to study other Web site designs to evaluate and select the best or latest features to incorporate into their Web site. In so doing, the Web site designers may easily infringe copyright by producing a derivative work.

In Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo, Inc., 964 F.2d. 965 (9th Cir. 1962), it was held that the “Game Genie” device that altered Nintendo’s videogame cartridges by enhancing the audiovisual displays without incorporating the original work in any permanent form did not create a derivative work. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 93]

4.3 Distribution right

Is the right to distribute i.e. sell, rent or lease copies of the copyrighted work. For e.g. the unauthorized printing or photocopying of textbooks for sale to students at a lower price or given free to students is an act of copyright infringement because the distribution right of the copyright owner is exercised.

In Marobie-Fl. Inc. v. National Association of Fire Equipment Distributors, 983 F. Supp. 1167 (N.D. Ill.), the court held that it was an infringement of copyright because unauthorized copies of the plaintiff’s electronic clipart files were placed on the defendant’s Web site for downloading by any Internet user. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 92]

Another aspect of the distribution right related to online materials is the practice of linking to other Web sites. Generally, the linking to the home page of another’s Web site by way of the Universal Resource Locator (URL) address is not an act of unauthorized distribution or copying within copyright laws. However, it is in the best interests of all parties involved to verify the Terms of Use found in other Web sites that may contain a clause prohibiting linking without expressed consent.

4.4 Public performance and public display rights

Public performance (e.g. recite, play, act, dance) and public display (e.g. show, exhibit, transmit directly or by way of film, slides, photography, television, projection, electronic medium, etc) is defined by copyright law as the performance and/or display of copyrighted work in a place open to or accessible to the public or semi-public, for e.g. a shopping mall, a museum, an art gallery, the lobby of an office building.

The Internet or cyberspace is a public place as any person in the world with Internet access can visit cyberspace.

In Columbia Pictures, Ind. v. Aveco, Inc., 800 F.2d. 59 (3rd Cir. 1986), the court held that the copyright owner’s public performance and public display rights were violated when the defendant improperly authorized the public performance of movies by renting videotapes and allowed customers to see the tapes in viewing rooms opened to the public. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 94]

The court also arrived at a similar decision of copyright infringement in Michaels v. Internet Entertainment Group, Inc., 5 F. Supp. 2d. 823 (C.D. Cal. 1998) where “making videotape footage available over the Internet without authorization and posting unauthorized copies of electronic clip art on Web pages violate the copyright owner’s exclusive statutory right of public display”. [Ferrera, 2004, p. 94]

5.0 Copyright infringement and legal remedies

As explained in the previous section, if one or more exclusive rights of the copyright owner is exercised by another without the consent of the copyright owner, it is an infringement of copyright.

The Malaysia Copyright Act 1987 defines copyright infringement as:

“(1) Copyright is infringed by any person who does, or causes any other person to do, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, an act the doing of which is controlled by copyright under this Act.

(2) Copyright is infringed by any person who, without the consent or licence of the owner of the copyright, imports an article into Malaysia for the purpose of --

(a) selling, letting for hire, or by way of trade, offering or exposing for sale or hire, the article;

(b) distributing the article --

(i) for the purpose of trade; or

(ii) for any other purpose to an extent that it will affect prejudicially the owner of the copyright; or

(c) by way of trade, exhibiting the article in public,

where he knows or ought reasonably to know that the making of the article was carried out without the consent or licence of the owner of the copyright.

(3) Copyright is infringed by any person who circumvents or causes any other person to circumvent any effective technological measures that are used by authors in connection with the exercise of their rights under this Act and that restrict acts, in respect of their works, which are not authorized by the authors concerned or permitted by law.

(4) Copyright is infringed by any person who knowingly performs any of the following acts knowing or having reasonable grounds to know that it will induce, enable, facilitate or conceal an infringement of any right under this Act:

(a) the removal or alteration of any electronic rights management information without authority;

(b) the distribution, importation for distribution or communication to the public, without authority, of works or copies of works knowing that electronic rights management information has been removed or altered without authority.

(5) For the purpose of subsection (4) and section 41, "rights management information" means information which identifies the works, the author of the work, the owner of any right in the work, or information about the terms and conditions of use of the work, any numbers or codes that represent such information, when any of these items of information is attached to a copy of a work or appears in connection with the communication of a work to the public.”

[Source: Malaysia Copyright Act 1987, Section 36: Infringements.]

Furthermore, in copyright infringement, “either the whole or a substantial part of the copyrighted work must be copied for the copying to amount to infringement”.

The originality of the part or parts taken must be proven in order to establish that a substantial part or parts had been copied. In Spectravest, Inc. v. Aperknit Ltd. (1998) FSR 161, it was held that “to determine liability, one should identify the part taken and separate from the defendant’s work and find out that originality of the part taken. It should also be shown that the defendant’s object in taking and using the part concerned is the same as that of the plaintiff’s, and the part taken is used by the defendant in a way which interferes with the sales of the original or competes with it”. [Colston, 1999, p.227]

For online materials, copyright infringement may involve the Internet Service Provider (ISP) if the ISP had facilitated the infringement. An ISP may be held liable for direct, vicarious or contributory infringement.

If an ISP had exercised the reproduction rights of the copyright owner without consent, the ISP may be guilty of direct infringement. If an ISP had financially gained from the infringement by another party and had the right to control and supervise the infringement, the ISP may be guilty of vicarious infringement.

Finally, if an ISP is found to have knowledge of the infringing activity and intentionally participated in it, the ISP may be guilty of contributory infringement.

Legal remedy or relief against copyright infringement generally takes the form of fines or penalties and/or imprisonment upon conviction.

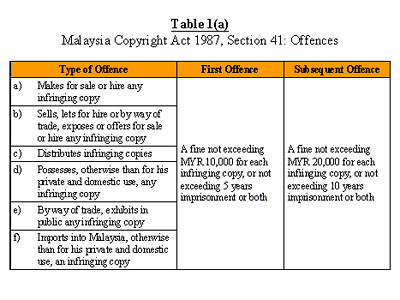

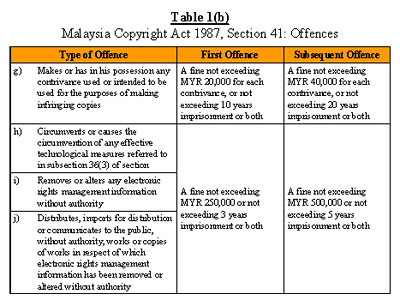

Section 41 of the Malaysia Copyright Act 1987 provides for fines ranging from Ringgit ten thousand to five hundred thousand, and/or imprisonment ranging from three to twenty years.

III. International Copyright Treaties

The relationship and effects between cyberspace and legal jurisdiction is not a straightforward subject. A Web site hosted in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia can be accessed or visited by any person in the world who has Internet access. Then, do courts in other countries have jurisdiction over copyright matters of the Web site of the Malaysian company? What happens when country A’s copyright laws differ from country B’s, or country A has inadequate copyright laws?

In order to achieve and provide an international minimum accepted copyright protection and recognition, and for the advancement of uniform copyright laws, several international treaties dealing with copyright exists:

- Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which includes the agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

- Universal Copyright Convention

- International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organisations (Rome Convention)

- Convention for the Protection of Producers of Phonograms Against Unauthorized Duplication of their Phonograms (Geneva Convention)

- World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) Copyright Treaty

- WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty

[Source: www.WIPO.int/copyright, www.WTO.org, www.UNESCO.org]

Many countries, including Malaysia, are members to the above treaties, but not all countries have signed or ratified all the terms of the treaties for implementation in the respective countries’ copyright laws.

However, by being a member of international copyright treaties, a country must legislate to achieve a minimum standard of copyright protection. In most cases, a country must also give copyright protection to materials from other member countries.

IV. Conclusion

Copyright law has not been made ineffective with the evolution of technology. Although the pace of digital technologies; related convergence of text, audio, video, images and animation; and “push” in terms of their application gaining influence in cyberspace is taking place at an unprecedented speed, past notions about copyright have been modified and will continue to be modified to encompass the cyberspace and new technologies.

In addition to major legislative changes and international cooperation to provide protection for online materials, novel business models, new protection technologies and even education in copyright laws may help make legislation more effective.

References:

Baumer, David & Poindexter, J. C. (2002). Cyberlaw and E-Commerce. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Colston, Catherine. (1999). Principles of Intellectual Property Law. London: Cavendish Publishing Ltd

Ferrera, Gerald R., Lichtenstein, Stephen D., Reder, Margo E.K., Bird, Robert C. & Schiano, William T. (2004). Cyberlaw: Text and Cases. Mason, Ohio: Thomson South-Western

Laws of Malaysia, Act 332: Copyright Act 1987 (incorporating latest amendment – Act A1139/2002). Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Law Publishers

Litman, J. (1996). “Copyright law and electronic access to information.” First Monday, Vol. 1 No. 4 www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue4/litman

Ryan, Timothy J. (2002). "Infringement.com: RIAA v. Napster and the War against Online Music Piracy." Arizona Law Review, Vol. 44 (2), p. 495 http://www.law.arizona.edu/Journals/ALR/ALR2002/vol442/Ryan_FINAL.pdf

Wienard, P. (1998). "Copyright in electronic information." www.farrer.co.uk/bulletins/ip/copyrigh.shtml