Dedicated to:

Scott A. Millington (of Australia)

– A good leader and a good boss

Best wishes in all your future endeavours!

***************************************************

-- Thomas Fuller

How does a person in an organisational structure with people manager responsibilities become a good boss? What does that person do that makes him 2 being judged a good boss by subordinates? The questions are simple to ask, but the answers may not immediately come to mind.

To be able to effectively manage people, people managers require leadership skills. So, do good leaders make good bosses? Let us first consider leaders and leadership.

I. What do Leaders do?

In any organisation, meetings, discussions and decision making are common daily activities. However, after plans are discussed and agreed, “…nothing is going to happen unless the leader’s teammates and subordinates want to move in the direction that’s been set. Making sure that happens is a big part of what leaders do.” says Gary Dessler [2001, p. 291]

Thus, leaders exhibit leadership, and leadership can be defined as, “influencing others to work willingly toward achieving objectives.” [Dessler, 2001, p. 291]

An enhanced definition of leadership is, “…the ability of leaders in organisations to lead people to achieve organisation goals and at the same time, create happy customers and employees.” [Tan, 2007, p. 62]

II. Leaders and Employee Motivation

Leaders fill many roles, and one of the many key challenges faced by leaders is employee motivation.

Motivation can be defined as “the forces acting upon or within a person that cause that person to expend effort to behave in a specific, goal-directed manner.” [Lewis et al, 2004, p. 460]

The process of motivation is complicated. However, leaders are particularly concerned about the relationship between motivation and performance i.e. what motivational approaches to take that would maximize performance? There is no singular approach or solution.

An understanding of the different approaches to motivation helps leaders to better understand and improve their interaction with their subordinates in order to strive for higher performance as a team.

1.0 The Needs-based Approach

Needs-based approach deals with “the factors within a person that energize, direct or stop behaviour.” [Lewis et al, 2004, p. 461]

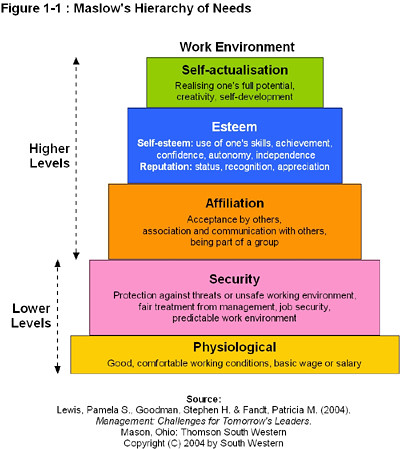

1.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

In 1943, Abraham Maslow, in his psychology paper A Theory of Human Motivation identified that a person has five fundamental needs – physiological, security, affiliation, esteem, and self-actualisation.

Physiological and security needs are categorised as lower-order needs and are typically satisfied externally, while affiliation, esteem and self-actualisation are categorised as higher-order needs which are typically satisfied internally.

Physiological needs

Physiological needs represent people’s basic needs such as food, water, and shelter. In the work environment, people with physiological needs are simply motivated by being able to own a job to meet basic necessities irrespective of the type of job they do, preserving their comfort level and avoidance of job pressure.

Security needs

People with security needs value a safe physical and emotional environment. Such people can be motivated by job security, grievance procedures, health insurance, fringe benefits and retirement plans.

Affiliation needs

Affiliation needs become important to people once their physiological and security needs are satisfied. People can be motivated by affiliation needs when they see their work as a means for developing interpersonal relationships and social networking.

Esteem needs

People with esteem needs are driven by personal feelings of achievement, recognition, respect and prestige. Such people can be motivated by developing their pride in their work and by rewards and recognition of their contribution to the organisation.

Self-actualisation needs

People with self-actualisation needs seek self-fulfillment and opportunities to achieve their full potential. Leaders can motivate such people by providing opportunities for them to lead special projects or assignments that capitalize on their strong self-drive and unique skills.

1.2 Herzberg’s Two-factor Model

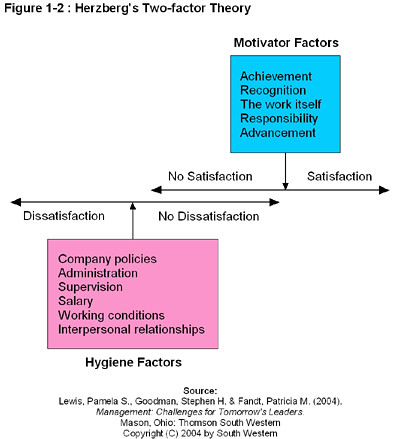

In the early 1960’s, Frederick Herzberg developed the two-factor model, also known as the motivation-hygiene theory, after discovering that job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction are independent of each other.

Motivator factors

According to Lewis et al, motivator factors relates to what a person actually do in their job and are associated with the person’s positive feelings about the job. Examples of motivator factors are the work itself, recognition, advancement, sense of achievement and responsibilities.

Hygiene factors

In contrast, hygiene factors such as company policies, administration, salary, and working conditions, relates to the work environment and are associated with the person’s negative feelings about the job. [2004, p. 464]

However, while motivator factors are typically considered and rated more important than hygiene factors by most people, it is yet to be proven beyond any doubts that motivator factors will increase work motivation for all people. Nevertheless, the initial step in motivating employees begins with addressing employee dissatisfaction.

Also, there are two contemporary issues with Herzberg’s two-factor model i.e. the on-going debate about the relationships between job satisfaction and performance, and the model’s classification of salary or pay as a hygiene factor – which means that salary is not a motivating factor.

On the relationships between job satisfaction and performance, researchers have shown:

- Job satisfaction causes job performance

- Job performance causes job satisfaction

- No relationship between job satisfaction and job performance

Thus, leaders or people managers should not adopt a simple cause-and-effect approach to the relationships between job satisfaction and performance.

Researchers have also shown that as society develops, societal and economic values changes, and money can become a very strong motivating factor.

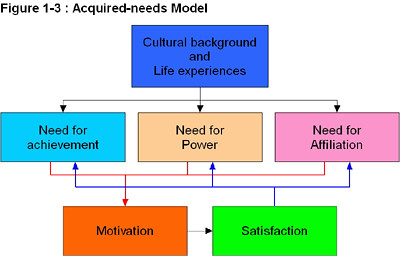

1.3 Acquired-needs Model

The acquired-needs model is based on the cultural background and the life experiences people gain and learn from. The model identifies three important needs in the work environment – need for achievement, power, and affiliation. People with a strong need will respond to motivation to satisfy that need.

Need for achievement

People with a need for achievement are typically high achievers who are driven to excel, take on challenging tasks, and strive for excellence. Such people are motivated by challenging tasks with high but achievable goals which can be broken down to provide them relatively immediate progress feedback.

Need for power

Need for power involves either personal power or institutional power. People have a need for power in order to influence and control their work environment. People needing personal power seek to dominate others in order to determine and control other people’s work outcomes. People with a need for institutional power seek to solve problems and advance organisational goals.

Need for affiliation

People with a need for affiliation are attracted to establish friendly and close interpersonal relationships, and enjoy working with other people.

Leaders should realize that people with a high need for achievement do not necessarily make good team players as they prefer to set their own goals and seek immediate performance feedback within a timeline that may be overly stressful for co-workers. However, in management succession planning and employee development, employees with a relatively balanced mix of a high need for achievement, institutional power, and affiliation may be potential future leaders in an organisation.

2.0 The Process Approach

The Process approach deals with the understanding of the cognitive processes within a person that influences his behaviour.

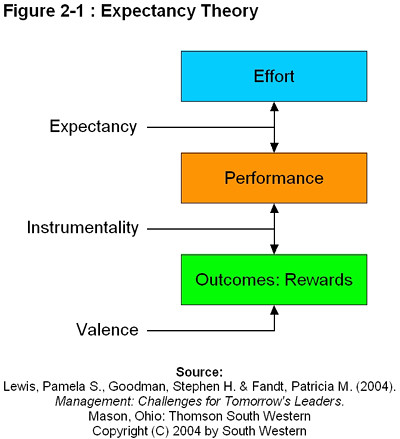

2.1 Expectancy Model

The expectancy model of motivation is based on three basic individual perceptions:

- Effort will lead to performance

- Rewards are attached to performance

- The rewards are valuable to the individual

Expectancy

This relates to a person’s belief that if a certain level of effort is expended, a certain level of performance will be achieved i.e. the relationship between effort and performance

Instrumentality

This is the next stage of perception or belief that when a specific level of performance is achieved, it will lead to a desired outcome.

Valence

Valence represents the value attached by a person to the outcome or rewards obtained.

Leaders should understand that the model seeks to explain that when people are given choices, they will select the choice that has the potential to give them the greatest reward i.e. the reward that they value most.

Thus, when applying motivation, it should be aligned to the person’s perceptions of what rewards are most important to them so that they willingly expend effort to achieve the performance desired by both subordinates and management.

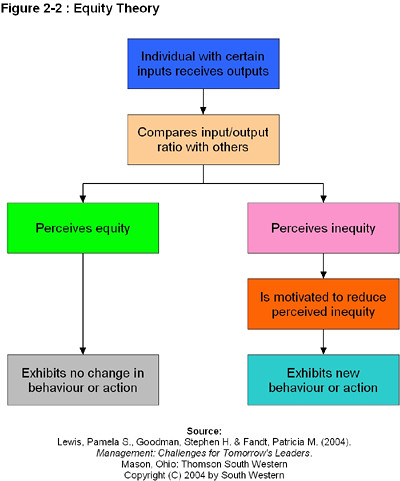

2.2 Equity (or Fairness) Model

Researchers have found that feelings of equity or inequity in the workplace are a major factor of job satisfaction or dissatisfaction among employees.

According to Lewis et al, “the equity model focuses on an individual’s feelings about how fairly he or she is treated in comparison with others.” [2004, p. 468]

The model says that people will compare the ratio of their contributions to their rewards against that of co-workers. If they perceive inequality then one of the following actions may be taken:

- Increase or decrease their work inputs to their perceived equity level, for e.g. if a person feels that he is underpaid, he may reduce his efforts by working shorter hours, decline more responsibility or work

- Psychologically distort comparison, for e.g. a person may distort how hard he has been working or how much he has been contributing to the organisation or increase the perception of importance of his job

- Change the person he is comparing to, for e.g. comparing one’s contribution to that of a lesser performing co-worker

- Change outcomes or rewards to gain equity, for e.g. by joining the company union that typically champions for increased welfare, pay, and better working conditions without the increase in employee inputs

- Leave the situation, for e.g. request for a transfer, or quit the job. This is usually the last resort when the employee feels that no other solution exists

Leaders need to be aware that their subordinates’ perception is an important factor in the equity theory of motivation. Perception of inequity is determined solely by a person’s interpretation and feelings of a given situation. For e.g. management may think that every employee will be happy with the annual pay increase or bonuses paid, but researchers have found that this is not the case. Some employees may feel that the rewards received do not equate to their past contributions and sacrifices.

Thus, leaders need to be aware of the existence of feelings of inequity among his subordinates, and to act to ensure that they feel equitably treated. One of several solutions is to establish regular one-to-one performance reviews to provide feedback, guidance and corrective measures. No employee appreciates being told only at the end of the year in the annual review that he has not been performing up to management expectations.

2.3 Goal Setting

“Goal setting as a motivation model is a process of increasing efficiency and effectiveness by specifying the desired outcomes toward which individuals, groups, departments, and organisation should work,” says Lewis et al.

“The major purposes of goal setting are:

- To guide and direct behaviour toward overall organisational goals and strategies

- To provide challenges and standards against which the individual can be assessed

- To define what is important and provide a framework for planning” [2004, p. 469]

In order for goal setting to be successful, leaders should follow the SMART rule – the goal must be:

- Specific or clear

- Measurable and not ambiguous

- Achievable

- Results-orientated

- Time-related i.e. have a reasonable time-frame for attainment

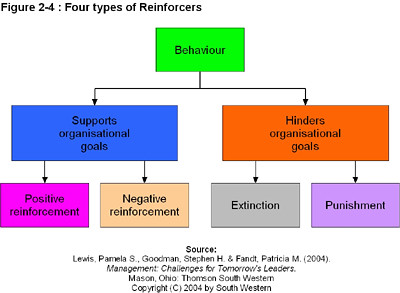

2.4 Reinforcement Theory or Behaviour Modification

The reinforcement theory is based on the concept that people will repeat behaviours that are rewarded and not behaviours that are punished.

Hence, leaders can motivate subordinates to strive for higher performance by reinforcing behaviours that support organisational goals

Positive reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is the application of a positive or rewarding action resulting from a desired behaviour, for e.g. accolades for a task well done, marketing excellence award for securing several difficult accounts, merit bonus for reducing significant costs for the company by successfully implementing new process improvements.

Negative reinforcement

Negative reinforcement promotes a desired behaviour by allowing escape from an undesirable consequence, for e.g. a 2 months suspension of driving license for driving through a red or stop light, getting penalised for clocking in late by more than 30 minutes.

Extinction

Extinction is the withdrawal of positive rewards or benefits for undesirable behaviour, for e.g. a slacking employee fails to receive his year-end bonus.

Punishment

Punishment is the application of a negative action for undesirable behaviour, for e.g. a reduction in the monthly entertainment allowance of a sales representative who is not achieving his sales quotas, a 2 weeks suspension without pay for being rude to a customer.

Leaders should take note that the formal application of reinforcement theory is also known as behaviour modification. Of late, critics have charged that behaviour modification is manipulative, tampers with human rights and freedom, and is unethical as the importance of corporate governance and corporate social responsibilities increases.

Furthermore, the use of punishment may cause unwanted consequences such as emotional harm, negative stress, and negative side effects, for e.g. fear, revenge.

3.0 Other Contemporary Motivational Approaches

3.1 Participative Management

Participative management involves all the activities where subordinates share a significant degree of responsibilities and decision-making with their supervisors, immediate managers or team leaders.

Participative management can increase job satisfaction and job performance by promoting a sense of appreciation and respect, acceptance and trust, and supports several key areas of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Herzberg’s two-factor theory, acquired-needs, expectancy, and equity models.

3.2 Rewarding Team Performance

Today, all if not, most organisations stress on team work or team contributions. Thus, it is also important to reward for team performance by rewarding the team members not as individuals but for each of their contribution to the collective performance of the team.

3.3 Money as a Motivating Factor

Research on money as a motivating factor is of particular interest to many organisations.

Money can be a motivator when:

- It is desired by the employee

- It is perceived as a means to acquire other things that is wanted or needed

- It is symbolic e.g. a measure of achievement or recognition

- A significant amount of money is clearly awarded for the desired behaviour or outcome

Money is not a motivator when:

- The desired productive behaviour is not defined

- The productive behaviour is poorly measured or there is no measurement

- The amount of money is too small to be appreciated

- It is perceived as an entitlement, for e.g. an overdue raise

III. Leaders and the Twelve ‘I’s of Leadership

In Practicing the ‘I’s of Leadership and Makings of a Good Leader, Dr. Victor Tan writes that it is important for leaders to master and practice the twelve ‘I’s of leadership in order to increase their leadership ability to motivate subordinates to achieve organisation goals, and at the same time, make them happy. With happy employees interacting with customers, in turn, customers can become happy with the higher level of attention and service quality they receive. [2007a, p. 62] [2007b, p. 64]

The twelve ‘I’s of leadership are:

- Inspire

It is important for a leader to be able to inspire his subordinates to strive for greater heights. Unmotivated employees will under-perform. Thus, leaders need to be able to inspire unmotivated employees to become passionate about their work and contribution. - Illuminate

Tackling issues and solving problems are part of everyday activities in the work environment. However, some issues and problems can be more difficult than others. A capable leader will be able to provide illumination to his subordinates to overcome the difficulties. - Illustrate

A good leader is able to communicate clearly with his subordinates. To be able to also provide illustrations in his communications will greatly improve his subordinates’ understanding of what is required to be achieved. - Involve

The motivational approach of participative management is based on the foundation of involvement. Good leaders recognize the need to involve their subordinates in tasks and projects, and to solicit their opinions and ideas in order to gain their commitment and support. - Innovate

Organisations today face greater competition and global challenges. In order for organisations to survive and achieve continuous profitable growth, effective leaders need to be able to motivate subordinates to introduce new ideas and processes i.e. develop an innovation culture. - Impart

Good leaders realize the importance and effectiveness of empowerment and coaching versus the outdated command and control approach to management. Thus, good leaders develop their subordinates by imparting their knowledge and experience to the extent that their subordinates can work independently of them. When their subordinates become as good as them, those subordinates become ready to take on bigger and more important roles in the organisation. - Influence

The power of leadership is not derived from great authority but from the degree of influence a leader has over others to get things done. The importance to focus on the circle of influence is well expounded by Stephen R. Covey in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. “The wider the circle of influence a leader has, the more effective he is in leading people towards achieving organisational goals.” [Tan, 2007, p. 64] - Initiate

“The only thing that is constant is change.” Does this statement sound familiar? Great leaders are not pro status quo but are effective change catalysts. The history of mankind is filled with great leaders who changed things. Capable leaders in an organisation recognizes the importance of initiating change instead of waiting for things to happen, and also knows how to involve their subordinates in initiating change. - Inquire

“Great leaders are inquisitive by nature”, says Dr. Victor Tan. [2007, p. 64] Capable leaders will always inquire about things in an organisation, for e.g. what is the basis of the sales forecast? What is the cause of the delta between actual results and planned? Why are employees exhibiting low morale lately? How do we motivate employees of different background and levels of experience? By asking, leaders seek to improve the organisation, and thus the long-term welfare and productivity of employees. - Improve

Complacency exists in every organisation and it becomes a great challenge for successful organisations to consistently achieve high performance. Good leaders need to be aware of and take action to reduce the complacency of subordinates. Good leaders must know how to motivate subordinates to continuously improve. Recognition of subordinates’ critical contributions or achievements and rewards needs to be given to reinforce the behaviour of continuous improvement. - Implement

In Makings of a Good Leader, Dr. Victor Tan says, “The value of leadership lies in getting people to implement ideas, suggestions or plans. No amount of analysis, strategizing or planning will make a company great if leaders do not get people to implement things.” [2007, p. 64] - Inculcate 3

Good leaders are able to encourage subordinates to think for themselves, self-motivate and strive for improvements and innovation. This can be achieved by inculcating a sense of continuous learning, probing problems, and process improvement among employees. [Wee, 2008, p. 1]

IV. Conclusion

A good leader knows why employee motivation is important, and will be able to motivate his subordinates in a positive and productive way. In turn, highly motivated subordinates become happy in meeting their work challenges and committed to strive to achieve the extraordinary.

According to Dr. Victor Tan, “The art of leadership lies not in firing people, but in firing up the enthusiasm of people to rise over the occasion and outperform their normal selves to achieve the extraordinary.” [2007, p. 62]

In the eyes of subordinates, a good leader makes a good boss.

1 Goodman, Ted. (1997). The Forbes Book of Business Quotations: 14,173 Thoughts on the Business of Life. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

2 All references to the masculine him / he / his, applies equally to the feminine her / she / hers

3 “Inculcate” was added to the ‘I’s of leadership by this author/blogger Chen Ming-fa

References:

Abell, Derek F. (1997). “Business is changing fast and so is the art of leading it” in Bickerstaffe, George. (Editor), Financial Times Mastering Management, p. 516 – 519. London, England: Pitman Publishing

Dessler, Gary. (2001). Management: Leading People and Organizations in the 21st Century. (2nd Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

Lewis, Pamela S., Goodman, Stephen H. & Fandt, Patricia M. (2004). Management: Challenges for Tomorrow’s Leaders. (4th Edition). Mason, OH: Thomson South Western

Robbins, Stephen P. & Coulter, Mary. (2003). Management. (7th Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

Tan, Victor S.L. (2007, December 1). “Practising the ‘I’s of leadership.” New Straits Times; p. 62

Tan, Victor S.L. (2007, December 8). “Makings of a good leader.” New Straits Times; p. 64

Useem, Michael. (1997). “Do leaders make a difference?” in Bickerstaffe, George. (Editor), Financial Times Mastering Management, p. 520 – 523. London, England: Pitman Publishing

Wee, David. (2008, July 26). “Don’t Tell Your Staff What to Do.” The Star; Metro Classifieds Central, p. 1

Wood, Jack D. (1997). “What makes a leader?” in Bickerstaffe, George. (Editor), Financial Times Mastering Management, p. 506 – 511. London, England: Pitman Publishing

Wood, Jack D. (1997). “The two sides of leadership” in Bickerstaffe, George. (Editor), Financial Times Mastering Management, p. 511 – 515. London, England: Pitman Publishing