1.0 Introduction

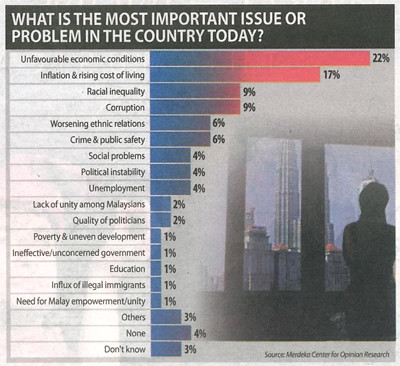

In the Fourth Quarter 2008 Peninsular Malaysia Voter Opinion Survey, respondents had ranked the top two concerns as:

- Unfavourable economic conditions; and

- Inflation and rising cost of living;

as shown in Figure 1-1 (Economy, 2009, p. 12). In another newspaper report, it said that, “basic food items like a 400g loaf of bread cost RM1.60 in 1993 and the price has risen 30 percent to RM2.10” (Chin et al, 2008, p. F20). Ex-farm live chicken per kg has risen by 52.3 percent from RM2.43 in 1988 to RM3.70. Rice – the 15 percent broken variety type, has risen by 34.6 percent from RM13.00 in 1998 to RM17.50, as shown in Figure 1-2. (Note: USD 1 = MYR 3.64 or RM 3.64 as at February 25, 2009).

Figure 1-1: What is the Most Important Issue or Problem in the Country Today?

Source:

“Economy, race main worries”

New Straits Times, 3 February 2009, p. 12

Figure 1-2: The Rising Cost of Living

Source:

“Spiralling out of reach” by Joseph Chin, Joseph Loh & Rashvinjeet S. Bedi

The Star, 22 June 2008, p. F20

From the income perspective, “while the economy has grown in the last 50 years – at 6 to 8 percent annually, salaries have not matched these types of growth. As such, most of the private sector companies still pay Third World salaries” (Gnanalingam, 2008). Furthermore, with the current global financial crisis that has drastically affected global economies, pay rises, if any, in 2009 will remain small (Paul Raj, 2008; Malaysian workers, 2008).

Managing salary and wage increases to a minimum may also be inline with Malaysia’s positioning as being resource rich, offering excellent infrastructure and availability of skilled yet low-cost labour to continue attracting FDI (Malaysia 14th preferred, 2008).

1.1 The Government’s call to buy more local products

The global financial crisis has caused the governments of several countries, for e.g. Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, United States and Peru, to encourage their citizens to buy more local products in order to save money (i.e. lower expenditure), stimulate the local economy and maintain some level of production capacities (In global, 2009; Indonesia mulls, 2009, p. B13; Ritikos & Ling, 2009, p. N4; Give local, 2009, p. 2; Gomez, 2009, p. 12; Bedi, 2009, p. F19; Liow: Use Malaysian, 2009; Millmow, 2009; President Garcia, 2009).

The “Buy Malaysian” call is especially important for Malaysia as 99.2 percent of the total numbers of businesses are SMEs, and they contribute 32 percent of the GDP with a workforce of 56.4 percent (Giving managers, 2009, p. 11). Furthermore, Malaysia’s exports had plunged by 28 percent in January 2009 (RM 38 billion) when compared to January 2008’s RM 53 billion – the worst decline in more than two decades (Damodaran, 2009, p. B2; Sarif, 2009, p. SBW10).

However, the WTO director-general has warned that such “measures by governments will jeopardise export sector jobs and risk setting the world on a damaging downward spiral of beggar-thy-neighbour protectionism” (Williams, 2009; Brazil may, 2009, p. B13; Trade Wars, 2009; Idris, 2009, p. SBW15).

===========================================================

Smart supermarket shopping just a click away

by Kristina George

(New Straits Times, March 14, 2009)

http://www.nst.com.my/Saturday/National/2504723/Article/index_html

This Web portal http://smartpengguna.my/default.aspx enables consumers to compare groceries and related products among the popular Malaysian supermarkets or hypermarkets. Currently, the comparative product / price information is only available for Klang Valley, Malaysia.

===========================================================

2.0 Market drivers

The escalating cost of living and the need to stretch the dollar has increased the opportunity and demand for lower priced consumer goods i.e. the market pull effect.

Retailers which are able to offer consumer goods at lower prices i.e. the market push effect, wins higher sales from consumers who are now increasingly prudent in their expenditure.

This market situation provides marketers the business opportunity to identify and develop alternative consumer goods to continue attracting consumers to their stores.

Other micro- and macro-economic factors that are fueling the demand for store brands (also known as private labels, retailer brands or house brands) as alternatives to manufacturer brands are:

- Global economic slowdown, escalating costs and rising inflation

- Global or regional expansion of large retailers e.g. Tesco, Carrefour

- Smaller manufacturers turning to contract manufacturing when their own, but weaker brands fail

- Increasing market competition

- Low cost as a differentiation strategy to achieve competitive advantage

- Retailers’ need to increase margins as operating cost increases

- Store brand products becoming more sophisticated as variety increases, and the quality and packaging improves

- Increasing willingness of consumers to consider lower price alternatives to stretch the household budget

3.0 Differentiation strategy – introduction of Store Brands

From a strategic approach, the large retailers e.g. hypermarkets are faced with:

- A segment of consumers demanding for alternative lower cost consumer goods

- The same segment of consumers expecting a minimal sacrifice in quality in lieu of the lower price

- The hypermarket’s need to increase margin with the reduced selling price

In essence, for the consumer, this can be translated to mean “low priced, respectably-branded consumer goods.” In other words, while consumers are increasingly attracted to lower priced consumer goods, they still require an acceptable assurance on the quality of those lower priced consumer goods.

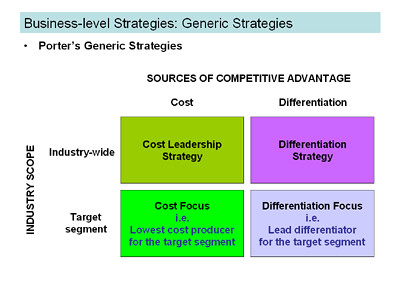

Based on Porter’s Generic Strategies, as shown in Figure 3-1 below, Carrefour, Giant or Tesco can decide to challenge each other to become the lowest cost player in the Malaysian hypermarket segment. Who succeeds in becoming the lowest cost leader will depend on its value chain being the most efficient and lowest cost.

Figure 3-1:

Striving to be the low cost leader can be effective when:

- The market comprises of many price-sensitive buyers

- Buyers do not care for differences between brands

- Many buyers with significant bargaining power exists

- There are few ways to achieve differentiation

Alternatively, Carrefour, Giant or Tesco can adopt a differentiation strategy instead of purely striving to become the lowest cost leader, because a strategy solely aiming to be the lowest cost leader is subject to the following risks:

- Competitors may imitate, thus driving overall industry profits down

- Buyer interest may swing to other differentiating features beside price

- Technological breakthroughs in the industry causing the strategy to become ineffective

Moreover, most, if not all cost leadership strategies involve some degree of differentiation. Since the product subject here is the respective hypermarkets’ store brands, thus, the brand name of the hypermarket can serve as a strategic form of differentiation, for e.g. Hypermarket X’s store brand is perceived to be of higher quality among all the hypermarkets.

With their respective well-known hypermarket name that they already enjoy – which typically is synonymous with offering manufacturer brand products at everyday low prices – being able to further lower the prices of everyday goods while maintaining the perception that quality is not compromised, creates a competitive advantage to retaining existing customers and acquiring new customers.

Consumer perception do place a value on the store brand product based on the hypermarket’s name. In other words, Consumer A perceives that Store Brand X from Hypermarket X may be of better or higher quality than Store Brand Y of Hypermarket Y.

To date, all three foreign-owned hypermarkets have introduced their respective store brands in Malaysia – Carrefour http://www.carrefour.com.my/carrefour_brands.php, Giant http://www.giant.com.my/store_brand.html, and Tesco http://www.tesco.com.my/article.cfm?id=43 (Hypermarket brands, 2008, p. 8).

The following advertisements (Figures 3-2, 3-3, 3-4, 3-5, 3-6, 3-7 and 3-8) by the aforementioned hypermarkets appeared in popular dailies to promote their respective store brands and to message the savings.

Figure 3-2: “Carrefour Products. Up to 30 percent cheaper compared to well known brands.”

Source: The Star, 11 June 2008, p. N7

Figure 3-3: “Cost Increase? Save more. Go Carrefour.”

Source: The Star, 4 July 2008, p. N21

Figure 3-4: Carrefour’s “Life’s Full of Choices.”

Source: Sunday Star, 29 March 2009, p. M5

Figure 3-5: “Giant Brand. Only RM1.99 each.”

Source: Sunday Star, 24 August 2008, p. N17

Figure 3-6: “Stretch your Ringgit. Spend less with Tesco.”

Source: The Star, 14 June 2008, p. N23

Figure 3-7: “New! Tesco Brand Electrical Range.”

Source: The Star, 28 June 2008, p. N26

Figure 3-8: “New! Tesco Brand Choices.”

Source: The Sun, 21 November 2008, p. 38

Furthermore, market reports by the Malaysia Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs are showing “that consumers are wising up on spending, and many are switching to alternative brands with comparable quality to branded goods. This is supported by the higher sales of house brands offered by the hypermarkets” (Loong, 2008, p. F27).

Datuk Shahrir Abdul Samad, minister of domestic trade and consumer affairs said, “Consumers are saying, let me look at quality and pay appropriate prices rather than going for the best brands all the time” (Loong, 2008, p. F27)

4.0 Market audit – the market size of Store Brands

According to a survey conducted last year by the Nielsen Company, “The demand for private-label products of local hypermarkets and supermarkets is increasing as more shoppers attempt to stretch their ringgit” (Kam, 2008, p. B7; More consumers, 2008, p. 50; Rising costs, 2008).

The Malaysian private label market from February to September 2008 was worth RM240 million as shown in Figure 4-1 (Kam, 2008, p. B7). This represents a 32 percent increase over the February to September 2007 period. As a comparison, branded goods or manufacturer brands grew only 15 percent for the comparative periods.

However, for the February to September 2008 period, manufacturer brands accounted for RM5.3 billion in sales. Thus, there is much room for store brands to grow from its 2008 sales of RM240 million.

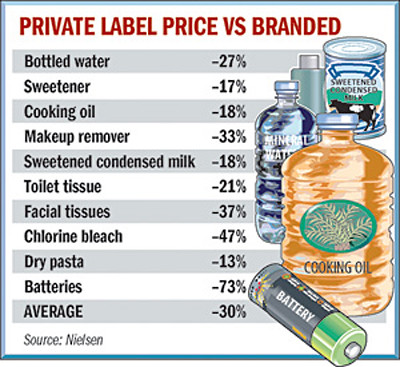

It is also worthwhile to note that the survey revealed or confirmed that, “on average, house brands are 30 percent cheaper than their branded counterparts” (More consumers, 2008, p. 50) as shown in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-1: Sales of Private Label Products vs. Branded Goods

Source:

“Consumers switching to private-label products” by Rachael Kam

The Star, 11 December 2008. p. B7

Figure 4-2: Private Label Price vs. Branded Goods Price

Source:

“More consumers opt for in-house brands” New Straits Times, 11 December 2008, p. 50

5.0 Strategies for hypermarkets to promote and grow their Store Brands

As discussed earlier, hypermarkets are facing:

- A segment of consumers demanding for alternative lower cost consumer goods

- The same segment of consumers expecting a minimal sacrifice in quality in lieu of the lower price

- The hypermarket’s need to increase margin with the reduced selling price

The key strategies hypermarkets can adopt are:

- Competing on price

- Competing on quality at lower prices

- Competing using portfolio segmentation

Competing on price

The key initial attraction of store brands to consumers is the lower price of the alternative product to the market leading manufacturer brands. The alternative product can be defined as, “the consumer perceived almost equivalent product” to the manufacturer brand.

In other words, for a lower price, consumers can accept alternative products or products which they perceive as almost the same as the manufacturer brand products.

Furthermore, with store brands, the hypermarkets are not only able to offer alternative products at a lower price but also earn a higher margin compared to the manufacturer brands which they sell side-by-side.

Figure 5-1 shows the store brand and manufacturer brand pricing model comparison. While the contract manufacturers of the store brands may charge the hypermarket higher costs, the contract manufacturers also earn lower margins themselves as they have no cost adders such as advertising and promotional expenditures to cover compared to the brand manufacturers.

Figure 5-1:

With the lower cost they obtain from contract manufacturers for their store brands, the hypermarkets can also earn a higher margin when they price the store brands close to manufacturer brands. The industry practice in Malaysia seems to be an average 30 percent price gap between store brands and manufacturer brands. This is further supported by the Nielsen Company audit of the private label market in Malaysia mentioned earlier.

Competing on quality at lower prices

In the previous paragraphs, I used the phrase “… almost equivalent product”. Why is almost equivalent important?

Although consumers may be shopping for lower price alternative products, but if the perceived quality of the store brand is in doubt, even the lower price may not significantly attract the consumers.

Thus, the store brand must be perceived as almost equivalent to the manufacturer brand which consumers have been using since trust or quality, and positive emotional bonding with the manufacturer brand have already been established.

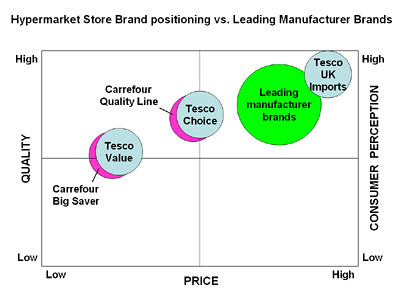

In this aspect, hypermarkets such as Tesco and Carrefour offer different categories for their store brands. Tesco offers Tesco Value and Tesco Choice as shown in Figure 5-2, and also the Tesco UK Imported range, while Carrefour offers Carrefour Big Saver and Carrefour Quality Line (NOTE: Carrefour Top Life are sports and fitness equipments, and Carrefour Harmonie are fabric products, i.e. non-grocery categories).

Figure 5-2: Store Brand Categories - Tesco example

Figure 5-3 shows how the hypermarkets position their store brand categories against manufacturer brands.

Figure 5-3:

Competing using portfolio segmentation

Hypermarkets can also use their store brands to compete against manufacturer brands by adopting a combination of portfolio segmentation strategy.

Portfolio segmentation is broadly based on price, category, and benefit:

- Price-based segmentation

Typically, this strategy uses two or three store brands to appeal to different price segments. Tesco uses this strategy with their Tesco Value offering basic need products at cheapest prices, Tesco Choice offering leading brand quality products at lower prices, and Tesco UK Imported range offering imported quality products for more discerning consumers.

- Category-based segmentation

Carrefour uses this type of portfolio segmentation by offering Carrefour store brands across product categories such as Carrefour Big Saver offering everyday basic products at cheapest prices, Carrefour Quality Line that emphasizes on product quality such as freshness, flavour, aroma, etc, Carrefour Top Life offering a range of sports and fitness equipments, and Carrefour Harmonie offering quality fabrics and textiles.

- Benefit-based segmentation

This form of segmentation strategy builds around consumers’ specific needs instead of appealing to consumers’ price sensitivity. For e.g., today, we find consumers being increasingly concerned about the type of fertilizers and chemicals used and long-term effects on health, thus, a market segment for natural and organic products is growing. Among the mentioned hypermarkets, Tesco UK Imported range also fits into this strategy by offering a higher quality benefit to consumers shopping for UK imported products.

6.0 Effects on Branded Goods and their manufacturers

How can brand manufacturers address the growing demand for store brands which competes for the same customer pool? How can brand manufacturers continue to supply and rely on large retailers e.g. the hypermarkets to promote the manufacturer brands when the hypermarkets are becoming more committed to promote their own store brands?

Manufacturer brands can consider and adopt the following strategies:

- Dual strategy – brand manufacturer continues producing its own brand and also the hypermarkets’ store brands

- Increase partnership effectiveness

- Increase the manufacturer brands’ value proposition

- Become more innovative

- Selectively fight store brands

Dual strategy

In markets where store brands have gained market leadership or controls the lion’s share of the market, it may make viable business sense for the brand manufacturers with idle production capacity to produce store brands for the hypermarkets.

By eliminating stagnant brands and extensions, and focusing on a smaller range of successful manufacturer brands, and additionally, producing store brands for the hypermarkets, the brand manufacturers can defend and increase market share and vis-à-vis their overall revenues and profitability.

A complete switchover may also be viable in the long-term, especially for the Tier 2 brand manufacturers that are not as successful as the Tier 1 brand manufacturers – they can become a dedicated store brand producer to the hypermarkets.

Increase the effectiveness of the partnership

Brand manufacturers should realize that a hypermarket also competes against other hypermarkets and large retailers. Thus, a hypermarket will need brand manufacturers to help them differentiate against another hypermarket or large retailer. With the large volume commitment that a hypermarket chain can provide, brand manufacturers should be able to customize certain products for the hypermarket to create product exclusivity via exclusive SKUs (e.g. a lower priced 4kg bottle of cooking oil instead of the standard 5kg bottle, or a tube of Colgate toothpaste with extra 20 percent content with a minimal price increase), and exclusive one-time offerings or limited editions on a mutually benefiting basis.

Another area where brand manufacturers can continue to value-add to the hypermarkets is in product assortment or product range. For hypermarkets to have their own store brands, volume commitment is the name of the game. Thus, the hypermarket will need to focus into specific categories of products where there is substantial volume or economies of scale created within its chain of hypermarkets. However, a brand manufacturer such as Proctor & Gamble (P&G) can easily offer the hypermarket an assortment of brands without the need of the hypermarket to build its own economies of scale simply because P&G already has the economies of scale.

Increase the value proposition of manufacturer brands

Brand manufacturers can increase the value proposition of their brands against store brands by:

- Creating greater product affinity to consumers’ perception (image and emotions)

- Managing the price gap between manufacturer brands and store brands of the same category

- Delivering customer satisfaction and expectation via a quality edge

Figure 6-1: Consumer Decision Making Process

Source: Deschamps and Nayak, 1995, p. 87

The above Figure 6-1 shows the consumer decision making relationship between image and emotional bonds, the price gap, and quality.

Consumers utilize information about the product or brand image, price and quality to assist and reinforce their purchase decisions. If the manufacturer brand lacks the right fit to the consumer’s desired product image and emotional bonding, the prospect is lost.

If it fits, then the consumer will consider the price gap between the manufacturer brand and the store brand. If the price gap is acceptable, the consumer purchases the manufacturer brand.

By using or consuming the manufacturer’s product, the consumer determines whether the product delivers the desired or expected performance i.e. delivering the desired level of customer satisfaction for the consumer to begin establishing a positive relationship with the manufacturer brand, for e.g. repeat the purchase and recommending the manufacturer brand to others (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007, pp. 195 – 196).

Increase product innovativeness

To continue maintaining their market leadership or defending their market share, brand manufacturers need to increase R&D expenditures to improve products and identify new product innovations.

From marketing management studies and research, the findings support the fact that, “as the number of new product launches in an industry increase, the share of private labels in the category declines” (Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007, p. 168).

Kumar & Steenkamp further says that, “Industries with a consistent history of new technology and brilliant innovation by brand manufacturers have powerful brands and relatively weak retailers” (2007, p. 168). New product technology and innovations are the corner stones of product differentiation strategies, and can create or attract profitable market segments. Differentiated products can act as an entry barrier for a market segment to the store brands.

Selectively fight Store Brands

The brand manufacturers, especially the market leading Tier 1 manufacturer brands can selectively fight the store brands in specific product categories i.e. track the store brand’s growth by product segment and compete against it market-by-market.

In fighting the store brands, the brand manufacturers will need to:

- Increase advertising and promotional budgets

- Reduce prices via sales promotional activities and loyalty programmes

- Introduce discount “fighter” brands

In the long-term, brand manufacturers must regularly re-examine their business and operational efficiency to maintain their core competencies such as:

- Decrease production costs by increasing production efficiency with the use of new technology

- Decrease operational costs by increasing operational and supply chain efficiency

- Reduce waste and idle time within the whole value chain beginning from the raw material suppliers to internal operations to logistics service providers to wholesalers/retailers

7.0 Conclusion

The economic and government influence, and the market drivers that helped to create the opportunity for the demand of store brands in Malaysia have been identified.

From the market audit conducted by the Nielsen Company, we can agree that there is a viable market for store brands in Malaysia, and ample opportunity for growth.

To develop the market for store brands, I have discussed the key issues and strategies the hypermarkets can undertake to promote their store brands and yet maintain strong business relationships with their suppliers i.e. the brand manufacturers.

For the brand manufacturers, the store brands are a threat to their business as more shelf space is being allocated to store brands since its demand is rapidly increasing. In this aspect, I have also discussed the key strategies brand manufacturers can consider in order to defend and continue growing their business.

However, the brand manufacturers which are most likely to suffer eroding sales or market share as the demand for store brands continue to accelerate are the Tier 2 brand manufacturers that presently have not been as successful to market their manufacturer brands compared to the market leading Tier 1 manufacturer brands.

A continuously improving knowledge-base and understanding of consumer needs and wants with respect to the changing economic conditions in the business environment will help ensure the survival and growth of both manufacturer brands and store brands, as in the end, consumers make the final decision to purchase what, where and when.

Thus, it is no surprise to find that manufacturer brand loyalty is still strong in Malaysia, based on a survey conducted by Synovate in November 2008. The survey spanned 18 countries and included 1,000 Malaysians aged 15 to 64 across all income levels (Chong, 2009, p. 53).

The brand loyalty survey results are tabulated as follows:

Figure 7-1:

While this may be good news for brand manufacturers, the fact that the demand for store brands is growing at more than double the rate of manufacturer brands (i.e. 32 percent vs. 15 percent) serves as a strong reminder that brand manufacturers must continue to innovate, maintain customer loyalty, and generate new customer demand.

References:

Aaker, David A. (1996). Building Strong Brands. New York, NY: The Free Press

Bedi, Rashvinjeet S. (February 1, 2009). “Save money, buy Malaysian.” The Star, p. F19

Blackwell, Roger D., Miniard, Paul W. and Engel, James F. (2006). Consumer Behavior, 19th Edition (International Student Edition). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western

Brazil may take ‘Buy American’ to WTO. (February 18, 2009). New Straits Times, p. B13

Chin, Joseph; Loh, Joseph and Bedi, Rashvinjeet S. (June 22, 2008). “Spiralling out of reach.” The Star, p. F20

Chong, Yvonne. (February 16 – 28, 2009). “Standing by their Brands.” Malaysian Business, pp. 53 – 54

Damodaran, Rupa. (March 7, 2009). “January exports plunge 27.8pc: Decline in value to RM 38.3 billion worse than market expectations.” New Straits Times, p. B2

Deschamps, Jean-Philip and Nayak, P. Ranganath. (1995). Product Juggernauts: How Companies Mobilize to Generate a Stream of Market Winners. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press

Economy, race main worries. (February 3, 2009). New Straits Times, p. 12

Give local producers a chance, consumers urged. (January 17, 2009). New Straits Times, p. 2

Giving managers the right skills. (February 17, 2009). New Straits Times, p. 11

Gnanalingam, G. (September 12, 2008). “Analysis: Malaysia Has First Class Infrastructure But Third World Salaries.” Bernama.com http://www.bernama.com/bernama/v5/newsbusiness.php?id=358773

Gomez, Jennifer. (January 29, 2009). “When buying local goes a long way.” New Straits Times, p. 12

Hypermarket brands a hit with the thrifty. (June 13, 2008). New Straits Times, p. 8

Idris, Izwan. (February 21, 2009). “In protectionism we do not trust.” The Star, p. SBW15

In global crisis, exporters turn to local market. (February 16, 2009). VietnamNet Bridge http://english.vietnamnet.vn/biz/2009/02/829230/

Indonesia mulls ‘use local’ decree. (February 17, 2009). New Straits Times, p. B13

Kam, Rachael. (December 11, 2008). “Consumers switching to private-label products: Cost-conscious buyers going for cheaper alternatives.” The Star, p. B7

Kapferer, Jean-Noel. (2008). The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term, 4th Edition. London, England: Kogan Page Ltd

Kotler, Philip and Keller, Kevin Lane. (2006). Marketing Management, 12th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Kumar, Nirmalya and Steenkamp, Jan-Benedict E.M. (2007). Private Label Strategy: How to Meet the Store Brand Challenge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press

Lincoln, Keith and Thomassen, Lars. (2008). Private Label: Turning the Retail Brand Threat into your Biggest Opportunity. London, England: Kogan Page Ltd

Liow: Use Malaysian goods. (March 18, 2009). The Star, p. N10

Loong, Meng Yee. (May 18, 2008). “Learn to stretch the Ringgit.” The Star, p. F27

Malaysia 14th preferred destination for FDI. (February 4, 2008). Malaysian Industrial Development Authority (MIDA) http://oldweb.mida.gov.my/beta/view.php?cat=53&scat=1991

Malaysian workers rally for better pay amid rising costs. (May 8, 2008). The China Post http://www.chinapost.com.tw/asia/malaysia/2008/05/08/155443/Malaysian-workers.htm

Millmow, Alex. (February 3, 2009). “Global crisis about to strangle us.” The Canberra Times http://www.canberratimes.com.au/news/local/news/opinion/global-crisis-about-to-strangle-us/1422891.aspx

More consumers opt for in-house brands. (December 11, 2008). New Straits Times, p. 50

Ng, Fintan. (February 28, 2009). “Soaring cost of living: Living alone in the Klang Valley can be expensive in troubled times.” The Star, p. SBW15

Paul Raj, Adeline. (December 10, 2008). “Smaller pay jumps ahead.” New Straits Times http://www.nst.com.my/Current_News/NST/Wednesday/National/2424246/Article/pppull_index_html

President García asks Peruvians to buy local products. (February 4, 2009). Andina http://www.andina.com.pe/Ingles/Noticia.aspx?id=MI377gFsSI4=

Rising costs pave way for private label sales in Malaysia. (December 5, 2008). The Nielsen Company http://my.nielsen.com/news/20081205.shtml

Ritikos, Jane and Ling, Sharon. (January 17, 2009). “Buy Malaysian goods, urges PM.” The Star, p. N4

Sarif, Edy. (March 7, 2009). “Exports down 28% in January.” The Star, p. SBW10

Trade Wars: Will Protectionism Win out over Recovery? (February 18, 2009). Knowledge@Wharton http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=2165

Upshaw, Lynn B. (1995). Building Brand Identity: A Strategy for Success in a Hostile Marketplace. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons

Williams, Frances. (February 3, 2009). “Lamy warns on ‘buy local’ measures.” Financial Times http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a013e78e-f20e-11dd-9678-0000779fd2ac.html?nclick_check=1