a) Characteristics of the Position, deals with:

3.2.4 Structural Hole

A thinking-man’s weblog in the interest of life-long learning and the free sharing of knowledge.

(2009, pp. 25-26)

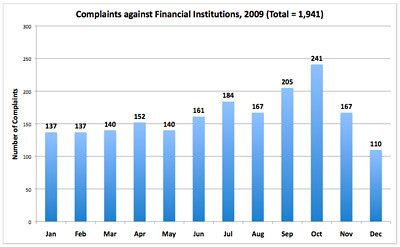

Figure 1-1: Number of Complaints against Malaysian Financial Institutions, 2009

(NCCC, 2009, p. 8)

So, are the banks responsible for the actions and behaviour of the debt-collection companies they engage? To answer the question, let us first better understand what is ethics and corporate social responsibility [a.k.a. Corporate Responsibility (CR)].

2.0 Ethics and CSR

2.1 Company Reputation and Financial Performance

A common but very important management excellence theme that Collins & Porras’ Built to Last, Collins’ Good to Great, and Brown & Turner’s The Admirable Company share is that a company’s reputation fuels its financial performance.

A company’s reputation vis-à-vis financial performance can be built from the following foundation components:

What are the benefits of gaining high reputation vis-à-vis high financial performance? “Sir Clive Thompson, then CEO of Rentokil – Britain’s most admired company in 1994, summarised the benefits as:

(Brown & Turner, 2008, p. 1)

Furthermore, “research has also shown that a good reputation:

(Brown & Turner, 2008, pp. 3-4)

2.2 Ethics

Ethics involves the study and practice of moral values, issues and choices. Ethics is concerned with what is right versus wrong, good versus bad and the “in-between” situations or issues generally known as the grey areas. Being ethical means complying to or upholding a set of moral principles, and this relates to discipline.

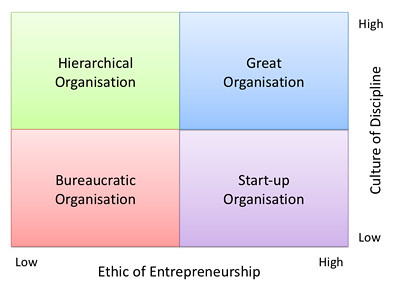

According to Jim Collins in Good to Great, high performing or great companies possesses a culture of discipline (Figure 2-1). “All companies have a culture, some companies have discipline, but few companies have a culture of discipline. When you have disciplined people, you don’t need hierarchy. When you have disciplined thought, you don’t need bureaucracy. When you have disciplined action, you don’t need excessive controls. When you combine a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship, you get the magical alchemy of great performance” (2008, p. 13 and pp. 120-123).

Figure 2-1: The Good-to-Great Matrix of Creative Discipline

(Collins, 2008, p. 122)

2.3 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Today, CSR is gaining attention and interest among leading Malaysian companies, the government and NGOs. While some companies are totally sold out on CSR by incorporating CSR as part of their business strategies, others are less enthusiastic, wondering if such efforts are just public relations stunts or corporate image-building activities.

If companies see CSR as mere philanthropy or charity and nothing more, then they do not yet clearly understand what CSR is. CSR, when properly understood, is not what you do with your money once you have made it but how you make your money.

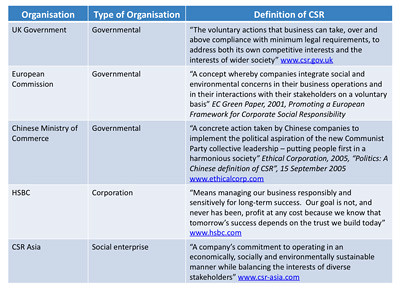

There is no single universally accepted definition of CSR. The vast amount of CSR literature, including corporate CSR reports, defines CSR differently, although the core elements of CSR are present in those many definitions. Some examples are listed in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1: Example Definitions of CSR

(Crane, Matten & Spence, 2008, pp. 6-7)

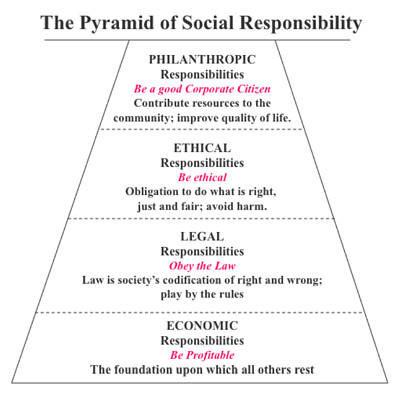

From the perspective of academic research and literature, “one of the most long-standing and widely cited definitions of CSR” is Archie Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR as per Figure 2-2 (Crane et al, 2008, pp. 57-58; Carroll, 1991, pp. 39-48).

Figure 2-2: Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR

Thus, we can argue that CSR needs to become part of the company’s DNA i.e. how it runs its business, how it manages its risks, how it strategizes for future survival and growth, and how it manages its relationships with multiple stakeholders i.e. the shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers, competitors, regulators and the community in which the company operates, and society as a whole.

Today, CSR is also important from the sustainability point of view i.e. how long can Earth or resources sustain our economic activities at the present economic rate and in the present form? Consider these simple examples – if a well-known restaurant is dependent on the sole proprietor, who is also the chef, and there are no succession plans, then that restaurant is not a sustainable business. It will only last as long as the sole proprietor/chef ‘s lifespan or ability to work. We all know that oil will run out one day in the future. Many of us will not be around to see that ‘one-day’. Thus, in the very long-term, oil companies are not sustainable.

CSR is an ethical framework that when used correctly and strategically, enables companies to develop innovative ways to create value and new ways of operations that may be more efficient in resource utilization and will benefit the company in the long-term.

There are six core characteristics that represent the essential features of CSR. They are:

(Crane et al, 2008, pp. 7-9)

To adopt CSR, most companies (e.g. banks and other financial institutions) can begin by focusing their CSR efforts or activities into four business dimensions i.e. the workplace, marketplace, community, and environment, and addressing example issues and challenges as follows:

i) The Marketplace

ii) The Workplace

iii) The Community

iv) The Environment

3.0 Stakeholder Engagement

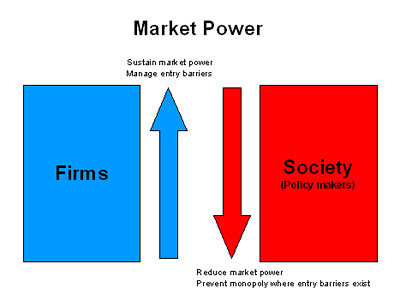

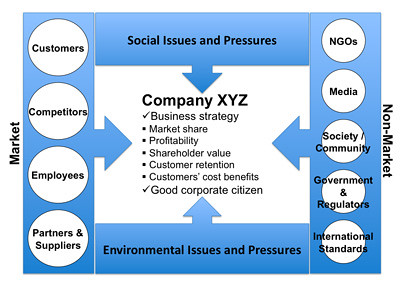

CSR does not only concern the company and society, but involves all of the company’s stakeholders.

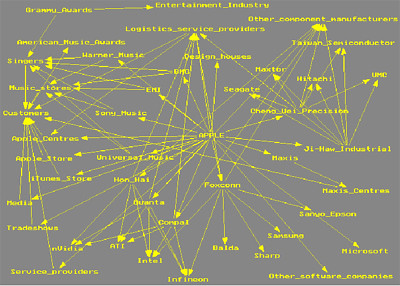

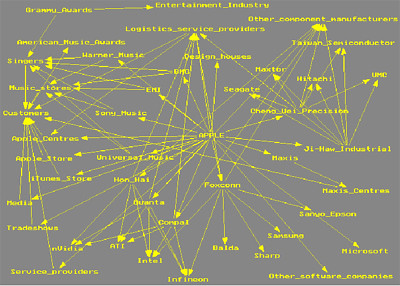

In Integrated Strategy: Market and Non-Market Components, Baron had categorized the stakeholders into two groups or components i.e. market and non-market (1995, pp. 47-48). The market component comprises the stakeholders such as customers, competitors, employees, and partners and suppliers, as shown in Figure 2-3. The non-market component comprises of NGOs, media, society or community, government, regulators, and environmental safety and standards organisations. Being concerned about or affected by social, ethical and professionalism issues, both the market and non-market components can exert differing degrees of social responsibility pressures or motivations on the company – in this case, the banks and debt-recovery service providers.

Figure 2-3: Stakeholders of a company: Motivations for CSR

The stakeholders, irrespective of whether they belong to the market or non-market components can be in the position of holding the company accountable for the social issues and resulting financial or economic impact. The stakeholders can also be champions for the company, slow the business progress of the company, or choose not to be involved. Should the company totally ignore the social responsibility pressures or motivations exerted by the stakeholders the consequences could prove disastrous in the long-term.

For e.g. if the debt-collectors engaged by the bank continues to use strong-arm tactics to collect debts and results in public police cases of assault and battery, serious injuries or deaths – accidental or otherwise, the negative publicity generated can cause serious reputational damage to the bank. Communities and society may easily perceive or conclude that the bank readily resorts to and condones acts of gangsterism to recover debts. Depending on the severity of the issue, NGOs, activists and even political parties can call for and orchestrate boycotts against the bank. The media and the Internet can easily be brought in to increase the negative publicity to a regional or global level creating adverse effects on the bank’s corporate image and reputation, customer confidence and support, and even shifting business to the bank’s competitors.

While the above has not yet happened in Malaysia, we can draw CSR concept similarities to some publicized real cases in other countries or industries such as:

In the Foxconn case, activists in Hong Kong had called for the boycott of the Apple iPhone because Foxconn, as a contract manufacturer, also manufactures the iPhone for Apple, Inc. (HK activists push, 2010).

The above cases and the earlier case of bank-appointed debt-collectors using strong-arm and harassment tactics in Malaysia are not surprising because it is a CSR myth if we think that “companies will compete in a ‘race to the top’ over ethics” (Blowfield & Murray, 2008, p. 354). In reality, “although companies may present themselves as socially responsible, there are many areas in which they deliberately pursue acts of social irresponsibility” (Blowfield & Murray, 2008, p. 354; Doane, 2005, p. 23-29).

4.0 Conclusions

We now return to the question, “Are the banks responsible for the actions and behaviour of the debt-collection companies they engage?” The answer is ‘Yes’.

Irrespective of CSR, banks are the key organisations in any country’s financial structure, and are expected to function with high standards of professionalism, trust and financial stability. Banks who officially or legally appoints or engage any other company as its business partner or supplier of products and services needs to ensure that the business partner or supplier is also of repute as it directly reflects upon the banks. When we include CSR, we have a stronger argument.

However, in Malaysia, CSR and corporate governance (CG) are only at the infancy stages when compared “to other Asian countries such as Singapore, Thailand and South Korea” (Haron, Ibrahim, Ismail, Quah, Kader Ali, Zainuddin & Nasruddin, 2007, p. 5). While there is awareness, the adoption, practice and reporting of CSR and CG is very slow or low.

From the research conducted by the Malaysia University of Science (Universiti Sains Malaysia) www.usm.my/bi, sponsored by the Malaysian Accountancy Research and Education Foundation (MAREF) http://www.maref.org.my/ and the Malaysian Institute of Integrity (IIM) http://www.iim.com.my/ (Haron, et al, 2007), out of the 200 Malaysian public-listed companies, only 28 responses were received for the CSR questionnaire, and 30 responses for the ethical orientations questionnaire, sent to the companies’ board of directors. Is this an indication that ethics and CSR are not important? Or there is nothing much to disclose when it comes to ethics and CSR, thus, the poor response? It is also interesting to note that none of the 200 public-listed companies included a bank (Haron et al, 2007, p. 1 and pp. 146-150).

Furthermore, NGOs in Malaysia are relatively weak as champions of the consumers given the existing laws on freedom of speech and expression, freedom of information, and freedom of assembly and association (SUARAM, 2009). This is further magnified by a poor consumer rights culture, and the fact that the main dailies or press/media are owned or controlled by the major political parties.

In summary, Malaysian banks (and other companies) do possess the power and ability to behave and perform much better, and consumers in Malaysia, including loan or payment defaulters, deserve to be treated in a professional and civic manner. Collectively, we need to march forward to increase our competitiveness, innovativeness, economic wealth and welfare, and ensure sustainability as a future developed nation. Thus, debt-collection strong-arm and harassment tactics are best left to the stone-age era.

Bibliography:

10th suicide case at Chinese firm. (2010). New Straits Times, 26 May, p. 27

Alfaro, Laura & Kim, Renee (2008) “U.S. Subprime Mortgage Crisis: Policy Reactions”. Harvard Business School Case #9-708-036, Rev: November 20, pp. 1-20

Baron, David P. (1995). “Integrated Strategy: Market and Non-Market Components.” California Management Review, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 47-65

Blowfield, Michael & Murray, Alan (2008) Corporate Responsibility: A Critical Introduction. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

Boatright, John R. (2007) Ethics and the Conduct of Business, Fifth Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

Boggan, Steve (2001). “Nike admits to mistakes over child labor”, Independent, UK, 20 October. Accessed from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/nike-admits-to-mistakes-over-child-labour-631975.html as at 19 February 2010

Brown, Richard & Turner, Paul (2008) The Admirable Company: Why Corporate Reputation Matters So Much and What It Takes to Be Ranked Among the Best. London, England: Profile Books

Carroll, Archie B. (1991, July-August). “The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders.” Business Horizons, pp. 39-48. Accessed from http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/faculty/dunnweb/rprnts.pyramidofcsr.pdf as at 7 July 2009

Cheah, Foo Seong & Lee, Leok Soon (2009) Corporate Governance in Malaysia: Principles and Practices. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: August Publishing

Colley, Jr., John L.; Doyle, Jacqueline L.; Logan, George W. & Stettinius, Wallace (2003) Corporate Governance. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Collins, Jim (2001) Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t. New York, NY: HarperCollins

Collins, Jim & Porras, Jerry I. (2002) Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. New York, NY: HarperBusiness

Crane, Andrew; Matten, Dirk & Spence, Laura J. (eds.) (2008) Corporate Social Responsibility: Readings and Cases in a Global Context. Abingdon, England: Routledge

CSR Asia: Corporate Social Responsibility in Asia. Accessed from http://www.csr-asia.com/index.php as at 7 July 2009

Cushman Jr., John H. (1998) “New York Times: Nike Pledges to End Child Labor And Apply U.S. Rules Abroad.” CorpWatch.org, 13 May. Accessed from http://www.corpwatch.org/article.php?id=12965 as at 19 February 2010

Doane, D. (2005) “The myth of CSR: The problem with assuming that companies can do well while also doing good is that markets don’t really work that way.” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Fall, pp. 23-29

Foxconn suicides shed light on workers. (2010). New Straits Times, 29 May, p. 24

Haron, Hasnah; Ibrahim, Daing Nasir; Ismail, Ishak; Quah, Chun Hoo; Kader Ali, Noor Nasir; Zainuddin, Yuserrie & Nasruddin, Ellisha (2007) “Governance, Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility of Public Listed Companies in Malaysia”, in Mohd Ali, Mohd Nizam; Alias, Abdul Samad; Mohamed, Nafsiah & Mohd Ishak, Mohd Rezaidi (eds.) (2007) Corporate Integrity Framework Research Monographs. [The Malaysian Accountancy, Research and Education Foundation (MAREF) – Malaysian Institute of Integrity (IIM) Commission Research Report] Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Malaysian Institute of Integrity

HK activists push for iPhone boycott after spate of suicides. (2010). The Star, 26 May, p. W38

ICCSR – International Centre of CSR. Nottingham University Business School. The University of Nottingham. Accessed from http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/business/ICCSR/ as at 7 July 2009

M. Raja (2007) “It hurts when an Indian bank loan goes bad.” Asia Times Online, 8 November. Accessed from http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/IK08Df03.html as at 26 May 2010

Mother sues bank for harassment in landmark legal action. (2007) DailyMail.co.uk, 18 April. Accessed from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-449293/Mother-sues-bank-harassment-landmark-legal-action.html as at 26 May 2010

Move to curb suicides. (2010). The Star, 27 May, p. W45

NCCC – National Consumer Complaints Centre (2009) Malaysia Complains: Never Underrate Consumers! (NCCC Annual Report 2009). Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: NCCC

Sharma, Hemender (2010) “Man alleges harassment by bank, commits suicide.” CNN – IBN Live, 17 May. Accessed from http://ibnlive.in.com/news/man-alleges-harassment-by-bank-commits-suicide/111620-3.html as at 26 May 2010

StarBiz-ICR Malaysia, The: Corporate Responsibility. Accessed from http://thestar.com.my/starbizicrm/default.asp as at 7 July 2009

SUARAM (2009) Malaysia Human Rights Report 2008: Civil and Political Rights. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: SUARAM Kommunikasi [Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM) / The Voice of Malaysian Citizens]

Suicide No. 10 at Foxconn. (2010). New Straits Times, 28 May, p. 29

Taiwan activists protest against Foxconn. (2010). The Star, 29 May, p. W39