Since the birth of the 21st century, cybercrime has increasingly become recognized as a problem that requires the attention of governments, law enforcement authorities and legal systems of leading Asia Pacific countries. The explosive growth of the Internet and adoption of digital technologies for electronic commerce, electronic data interchange and electronic communication needs in the Asia Pacific region has also brought about an increase in cybercrimes.

Advanced countries in the West with highly developed information and communication technology infrastructures are also forced to constantly review the adequacy of their legal systems to deal with cybercrime. Other countries in South East Asia, such as Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia, developing their information and communication technology system from a less advanced base are similarly forced to review the adequacy of their existing legal systems.

Existing criminal law, supported with commercial and intellectual property protection law may already inhibit a range of cyberspace misconduct. However, gaps and inadequacies of existing traditional laws necessitate the consideration and introduction of more specific laws to address cybercrime.

II. What is Cybercrime?

In Grabosky & Smith (1998), the following categories of crime were found to be emerging in the digital age:

- Illegal telecommunications interception (e.g. hacking, cracking, data manipulation)

- Electronic vandalism

- Electronic terrorism (e.g. viruses, denial-of-service attacks, spamming)

- Theft of data and communications services

- Telecommunications and associated intellectual property piracy

- Electronic distribution of pornography

- Electronic fraud (e.g. phishing)

- Electronic funds transfer crime

- Money laundering

Collectively, these crimes are referred to as “cybercrimes”.

How serious or damaging is cybercrime? Warren & Streeter (2005) reported that, “the Internet has become a non-stop source of crime stories. The Bank of America revealed it lost computer tapes containing financial data on 1.2 million federal workers, including US senators, and British police recently charged 28 people with involvement in a sophisticated identity fraud racket that swindled almost 2 million pounds from more than 100 private bank accounts.” “The US Federal Trade Commission revealed last year that 10 million US citizens had fallen victim to identity theft at a total cost of USD 50 billion, and that 2 million people were conned by phishing attacks.”

Phishing [Sullivan, 2004, p.24], first detected in 1996, has exploded in the last two years because it is easy to produce and easy to fall for. Fraudsters send fake or spoof e-mail to bank customers to obtain their logins and passwords or to trick them into visiting fake banking websites.

On the home front, cybercrime rate is on the rise [Rising cybercrime, 2004, p.2]. Chia Kwang Chye, former deputy minister of internal security said, “117 cases involving MYR451,000 in losses were taken to court, under the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998” for the period of January to September 2004, compared to 35 cases in 2003.

Chia also said that 857 cases were charged in court in 2003 under the Computer Crimes Act 1997, with loses totaling MYR2.9 million, while 355 cases were brought to court from January to September 2004.

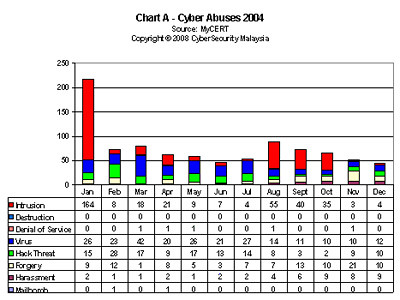

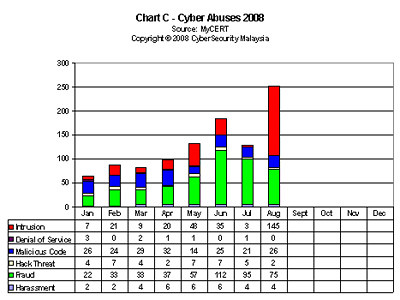

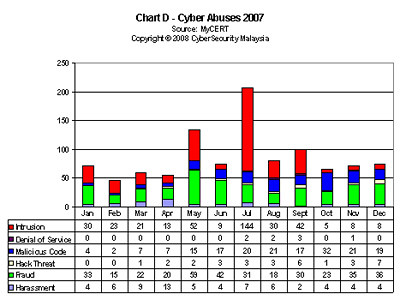

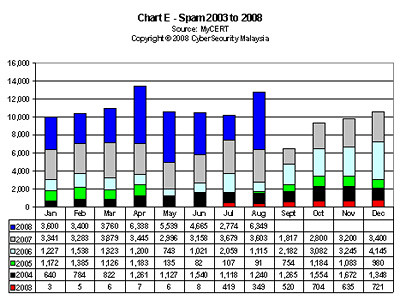

In its first quarter 2004 report, the Malaysian Computer Emergency Response Team (MyCERT) said that, “Internet vandals went wild early this year defacing hundreds of Malaysian websites, with public sector sites the main victims.” [Sharif, 2004, p.3] The following charts A to E provide some statistics.

While some of these crimes can be prosecuted to a certain extend with the combination of existing criminal, commercial and intellectual property laws, the experience of many jurisdictions is that additional legislation is often required to address these Internet, computer systems and electronic communication related crimes.

III. What is Cybertort?

Before I embark on defining “cybertort”, let us first understand what is defined as a tort. “A tort is a wrong. It can be a spoken wrong or an act (action), or a nonaction (carelessness) that is wrong, with injury inflicted on a person or property.” [Baumer & Poindexter, 2002, p.119]

Thus, there is tortious liability when a tort is committed, and I can define tortious liability as, “Tortious liability arises from the breach of a duty primarily fixed by the law; this duty is towards persons generally and its breach is redressable by an action for unliquidated damages.” [Lee, 2001, p.189]

Torts include issues such as:

- Trepass to a person

- Trespass to land

- Trespass to nuisance

- Trespass to goods

- Negligence

- Defamation

The tort most relevant to cyberspace is defamation. Defamation may be defined as, “Oral or written statements that wrongfully harm a person’s reputation.” [Ferrera et al, 2004, p.345] Defamation committed orally is known as slander, and defamation committed in writing is known as libel.

Therefore, torts committed in cyberspace (or the Internet and/or the World Wide Web) are known as cybertorts. Defamation can easily be committed in the cyberspace via e-mails or electronic mails, articles or postings in Weblogs, messages and/or videos in social networking sites such as YouTube, Facebook, etc.

The legal remedy or suit against defamation requires several elements of proof such as:

- A false statement of fact, not opinion, about the plaintiff

- The publication of the false statement without a privilege to do so

- Intentional or due to negligence

- Damages – actual and/or presumed suffered by the plaintiff

IV. The Cyberlaws of Malaysia

With the arrival of the digital economy or knowledge economy as embraced by Malaysia, and the birth of the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC), new laws introduced in 1997 covering computer crimes, digital signature, telemedicine, copyright were promoted by the MSC’s custodian – the Multimedia Development Corporation as a package of cyberlaws.

The cyberlaws are:

i) The Computer Crimes Act 1997

This Act provides law enforcers with a framework that defines illegal access, interception, and use of computers and information; standards for service providers; and outlines potential penalties for infractions.

ii) The Digital Signature Act 1997

Regulates the legal recognition and authentication of the originator of electronic document. This Act enables businesses and the community to use electronic signatures instead of their hand-written counterparts in legal and business transactions.

iii) The Telemedicine Act 1997

This Act empowers medical practitioners to provide medical services from remote locations using electronic medical data and prescription standards, in the knowledge that their treatment will be covered under insurance schemes. However, this Act is yet to be implemented.

iv) The Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997

This Act gives multimedia developers full intellectual property protection through the on-line registration of works, licensing, and royalty collection. Especially, the Act reinforces an author's work cannot be presented as the work of another, by adding a provision that the work must be identified as created by the author.

It was also decided that a regulatory body entrusted with the role to implement and promote the national objectives of the Malaysian Government for the communications and multimedia sector was needed. Hence, in 1998, another two acts were passed.

v) The Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission Act 1998

Provide for the establishment of the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), a single regulatory body for an emerging and converging communications and multimedia industry. This Act gives the MCMC the power among other things, to supervise and regulate communications and multimedia activities in Malaysia and to enforce the relevant laws.

vi) The Communication and Multimedia Act 1998

The most significant legislation brought into force on April 1, 1999. This legislation provides the policy and regulatory framework for convergence of the telecommunications, broadcasting and computer industries. The Act is based on the basic principles of transparency and clarity; more competition and less regulation; bias towards generic rules; regulatory forbearances; emphasis on process rather than content; administrative and sector transparency; and industry self-regulation.

In addition, the government is also in the process of formulating another legislation presently called the Personal Data Protection Bill [Surin, 2003b, p.16-18]. This law will provide assurance of privacy of personal data. It will address the issues of collection, processing, maintenance and utilization of personal data.

The above cyberlaws serve two central purposes:

- To bolster intellectual property rights; and

- To create the right environment for the multimedia industry and for online transactions or electronic commerce to thrive in a continuously and increasingly competitive business environment

V. Adequacy of Legislation

In general, countries can be categorised according to whether they have:

- Basic criminal and commercial laws

- A developed system of intellectual property laws

- Legislation directed specifically at computers and electronic commerce

Malaysia may be observed to fall within one or more of these categories, mostly satisfying the second category and having made some progress towards the third. Whether the existing legal system in any country can adequately address cybercrime depends on the precise scope and interaction of its criminal, commercial, intellectual property and computer-related laws.

The rapid development of information and communication technology and emerging electronic commerce pose challenges for the existing laws of Malaysia. Some key challenges created by the Internet or cyberspace in the enactment of statutes and development of the common law includes the identification of legal entities in cyberspace, the need to protect privacy and the issue of digital signatures that require close regulation.

1.0 Absence of Territorial Borders in Cyberspace

The jurisdiction of courts is based on the concept of territoriality. While we may call “cyberspace” in the singular, it is however, not a singular or distinct “place” but made up of many virtual locations constituting several business models from the real world that are recreated in computer-mediated communication infrastructures. Cyberspace crosses geographical and jurisdictional boundaries as we know it due to the cost, ease and speed of electronic transmission on the Internet that is almost entirely independent of physical location.

A major challenge for the law is created by the cross-boundary nature of cyberspace or in other words, its borderless nature. In relation to law, Johnson and Post (1996) outlined some cross-border issues:

- The power of local governments to assert control over online behaviour

- The effects of online behaviour on individuals or things

- The legitimacy of the efforts of a local sovereign to enforce rules applicable to global phenomena

- The ability of physical location to give notification of which set of rules apply for any given situation. Regional or national regulation by market authorities and other self-regulatory organisations are clearly less than satisfactory for the internationally active cross-border Internet

Hence, new legislation able to address cyberspace issues such as accountability and governance; proper usage, orderly conduct, structure and development; and cybercrime became very important due to the undermining of the feasibility and legitimacy of applying laws based on geographic boundaries.

Malaysia’s cyberlaws, as outlined in the previous section, governs the behaviour, content, business transactions, privacy, defamation, contracts, and intellectual property rights in a cyberspace environment, committed within and outside of Malaysia.

The Communication and Multimedia Act 1998, Section 4: Territorial and extra-territorial application provides for:

(1) This Act and its subsidiary legislation apply both within and outside Malaysia.

(2) Notwithstanding subsection (1), this Act and its subsidiary legislation shall apply to any person beyond the geographical limits 6f Malaysia and her territorial waters if such person –

(a) is a licensee under this Act; or

(b) provides or will provide relevant facilities or services under this Act in a place within Malaysia.

The Computer Crimes Act 1997, Section 9: Territorial scope of offences under this Act provides for:

(1) The provisions of this Act shall, in relation to any person, whatever his nationality or citizenship, have effect outside as well as within Malaysia, and where an offence under this Act is committed by any person in any place outside Malaysia, he may be dealt with in respect of such offence as if it was committed at any place within Malaysia.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1), this Act shall apply if, for the offence in question, the computer, program or data was in Malaysia or capable of being connected to or sent to or used by or with a computer in Malaysia at the material time.

2.0 Computer and Computer-related Offence Provisions

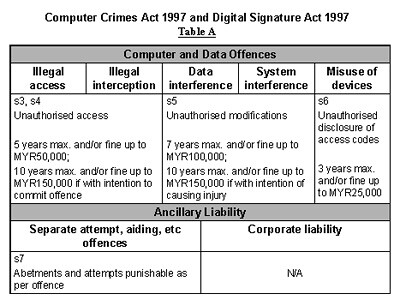

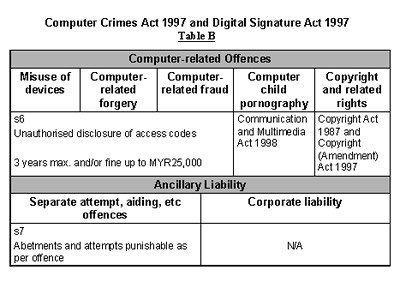

The following Tables A and B presents a comparative analysis of computer and computer-related offence provisions available in Malaysia.

From the above, arguably, Malaysia can be considered as having a quite respectable segregation or classification of computer offences.

Computer-related offences

Although fraud and forgery can be prosecuted under the commercial and criminal laws whether committed using a computer or by more traditional paper-based means, it is good for Malaysia to have specific fraud and forgery offences addressed in the main computer crime legislation.

Ancillary liability

While not in the main computer crime law, computer child pornography, and copyright and related-rights are addressed in the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 and Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997 respectively, which are collectively a part of Malaysia’s cyberlaws.

Special enforcement units

Recognising the highly specialised knowledge and skills required for investigation and evidence gathering in relation to cybercrime, some countries have moved towards setting up specialised computer crime units within their law enforcement agencies, for e.g.

- HITEC (HI-tech crime Technical Expert Center) established to act as a “cyberpolice force” by the National Police Agency of Japan

http://www.npa.go.jp/cyber/english/policy/hightech_prog.htm

http://www.npa.go.jp/english/index.htm - Korean National Police Agency’s Cyber Terrorism Response Center and recently announced General Investigation Center of Computer Crimes under the Prosecutor-General’s Office

In this aspect, Malaysia does not yet have a specialist cybercrime law enforcement unit, thus cybercrimes are referred to the traditional Commercial Crimes department of the police force.

Forfeiture and/or Restitution

Apart from the imposition of terms of imprisonment and fines, cybercrime legislation can empower courts to order the forfeiture of equipment used and/or assets acquired, or to require restitution to victims. For e.g., in Taiwan there is a statutory maximum for damages that can be awarded to injured persons under the Computer Processing Personal Information Protection Law. In the Philippines, maximum penalties imposed for hacking or cracking under the Electronic Commerce Act are commensurate to the damage incurred.

In Malaysia, forfeiture and/or restitution is not clearly defined in the cyberlaws and usually falls back upon existing commercial and criminal laws.

Undercover Surveillance/Search and Seizure

Standard search and seizure powers for the investigation of criminal offences may not extend to the investigation of computer data or the interception and covert surveillance of electronic transmissions such as e-mail. Cybercrime legislation in Malaysia should provide for expanding the range of investigatory powers available to law enforcement.

International Agreements

There are currently no international agreements on the scale of United Nations conventions or treaties (e.g. for international trade, there is the World Trade Organisation) in relation to cybercrimes that Malaysia can actively participate in and/or contribute to. Such a platform can provide excellent benefits to Malaysia in formulating and advancing cyberlaws.

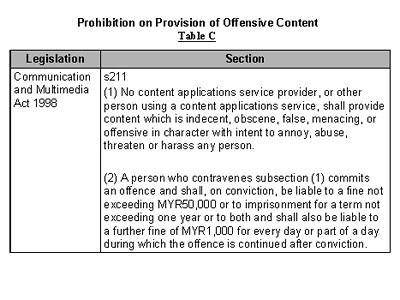

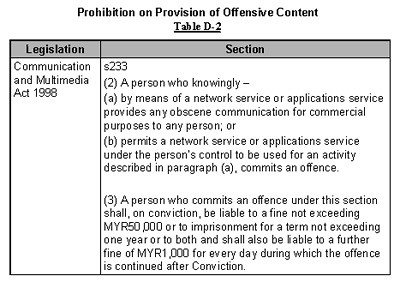

3.0 Prohibition on Provision of Offensive Content

Offensive content includes but not limited to pornography, indecent or unsuitable content for children, objectionable content, and defamatory articles and/or statements

The Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 provides legislation against offensive content and the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) is thus empowered to act against offensive content by way of written requests to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to take action against offensive content.

The following Tables C, D-1, D-2 and E summarises the relevant sections of the Act.

4.0 Intellectual Property Rights Offence Provisions

There is considerable overlap between cybercrime laws and intellectual property laws. For e.g., computer hardware may constitute a patentable invention, a registered design, or be protected under legislation relating to electronic circuit layouts. Computer software may similarly be protected under copyright law, and likewise with data and information transmitted or stored on files.

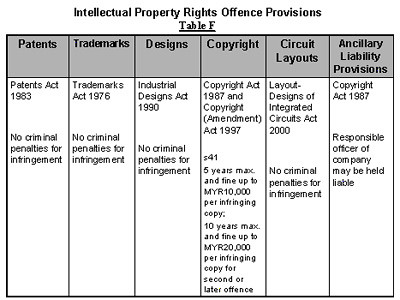

The following Table F shows the intellectual property rights offence provisions available in Malaysia.

Offence Classification

The classification of intellectual property laws into patents, trademarks, designs, copyright and computer circuit layouts is fairly standard, and it is somewhat worrisome that in Malaysia, most of the intellectual property rights legislation does not recognise infringement as a criminal offence other than those provided for under the Copyright Act 1987 and Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997.

Computer Software

Unauthorised duplication of computer software (except to make a back-up copy for personal use) is an infringement under Malaysia copyright laws. The Copyright Act 1987 was amended to give multimedia developers full intellectual property protection through the on-line registration of works, licensing, and royalty collection. The Amendment Act reinforces an author's work cannot be presented as the work of another, by adding a provision that the work must be identified as created by the author.

Optical Disc Piracy

Very few Asia-Pacific countries or jurisdictions have laws explicitly relating to optical disc piracy. A good example is Hong Kong’s Prevention of Copyright Piracy Ordinance, which prohibits the manufacture of optical discs without a valid licence, punishable by a fine of HK$500,000 and imprisonment for two years on a first conviction; and HK$1,000,000 and four years imprisonment on a subsequent conviction.

Malaysia’s Optical Discs Act 2000 came into force on September 15, 2000. Section 26 provides for:

Section 26. Penalty.

(1) Any person who commits an offence under Part III except under section 15 shall on conviction be liable –

(a) if such person is a body corporate, to a fine not exceeding five hundred thousand ringgit, and for a second or subsequent offence to a fine not exceeding one million ringgit; or

(b) if such person is not a body corporate, to a fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to both, and for a second or subsequent offence to a fine not exceeding five hundred thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six years or both.

(2) Where a person being a director, manager, secretary or other similar officer of a body corporate is guilty of an offence under subsection (1) by virtue of section 30, he shall on conviction be liable to the penalty provided for in paragraph (1) (b).

Circumvention of Technological Protection Measures

Offence provisions in relation to the circumvention of technological protection measures such as encryption devices, user identification and electronic rights management information regimes are already introduced in leading Asia-Pacific countries such as Singapore, Australia, Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan.

In this area, Malaysia is also not trailing. The Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997 provides for fines of up to MYR250,000 and/or imprisonment for up to three years for the first offence, or MYR500,000 and/or five years for subsequent offences.

International Agreements

International agreements for the protection of industrial and intellectual property date back over 100 years. Malaysia is a member or signatory of the following main instruments administered by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

- Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property 1883 (Malaysia’s membership: January 1989)

- Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886 (Malaysia’s membership: October 1990)

- Convention establishing the World Intellectual Property Organisation 1970 (Malaysia’s membership: January 1989)

- Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights 1994 (Malaysia membership: January 1995)

Sources:

WIPO http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/

UNESCO http://www.unesco.org

WTO http://www.wto.org)

VI. Conclusion

Cybercrime legislation in Malaysia is still in the early stages of development, and exhibits overlap with general criminal, commercial and intellectual property laws. This is not surprising given the different historical, social and political contexts and needs within which these laws have evolved, and the differing levels of technological development compared to other countries.

However, it is a fact that cybercrime knows no national borders and, as a result, defences against the threats increasingly posed to computer and information infrastructures can only be as strong as the weaker links in the chain. Therefore, it is important for Malaysia to continually assess the adequacy of the cyberlaws and, where deficiencies can be identified, to reform those laws appropriately and quickly.

Therefore, it was a let down when Datuk Dr. Rais Yatim, former minister in the Prime Minister’s department, announced at the third MSC International Cyberlaws Conference held from March 2 to 3, 2004 that the three draft cyberlaws, namely the Personal Data Protection Act, Electronic Transactions Act and the Electronic Government Activities Act will be delayed [Khalid & Moreira, 2004, p.3].

“The first would regulate the collection, possession, processing and use of personal data, and ensure there are adequate measures for the security, privacy and handling of personal information. It aims to raise public confidence in conducting electronic transactions without their privacy being violated.”

“The Electronic Transactions Act is primarily targeted at boosting e-commerce by providing legal recognition of electronic transactions, including e-commerce transactions.”

“The Electronic Government Activities Act seeks to establish common protocols for electronic interaction between the Government and the public.”

Thus, these draft legislation are important additions to Malaysia’s cyberlaws and any further delays will eventually become detrimental for Malaysia to competitively position herself in an increasingly globalising economy. (The Malaysian government had released a draft version of the proposed Personal Data Protection Act for public comment in November 2000.)

Lawyer Wong Shiou Sien, a speaker at the conference, argued, “Despite being among the first countries in the world to introduce cyberlaws, Malaysia cannot afford to remain at a standstill. New developments in technology, products, and services related to wireless content will keep raising new legal and regulatory issues.” [Khalid & Moreira, 2004, p.2]

While there is no single model to be emulated in this process, guidance can be gained from legislation in force in countries or jurisdictions with longer experience of the threat, management and prosecution of cybercrimes, and the promotion of the effective and efficient use of cyberspace to increase the competitive advantage of our nation Malaysia.

References:

MyCERT statistics http://www.mycert.org.my/en/index.html

Computer Crimes Act 1997

Digital Signature Act 1997

Communication and Multimedia Act 1997

Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission Act 1997

Telemedicine Act 1997

Copyright Act 1987

Copyright (Amendment) Act 1997

Patents Act 1983

Trademarks Act 1976

Industrial Designs Act 1990

Optical Discs Act 2000

Layout-Designs of Integrated Circuits Act 2000

Baumer, David & Poindexter, J. C. (2002). Cyberlaw and E-Commerce. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Endeshaw, Assafa (2001). Internet and E-Commerce Law: With a Focus on Asia-Pacific. Singapore: Prentice-Hall

Ferrera, Gerald R., Lichtenstein, Stephen D., Reder, Margo E. K., Bird, Robert C. & Schiano, William T . (2004). Cyberlaw: Text and Cases. (2nd Edition). Mason, Ohio: Thomson South-Western

Grabosky, P. N. & Smith, R. G. (1998). Crime in the Digital Age: Controlling Telecommunications and Cyberspace Illegalities. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers/Federation Press

Johnson D. R. & Post D. G. (1996). "Law and Borders: The Rise of Law in Cyberspace." Stanford Law Review, Vol. 48, p.1367

Khalid, H. Amir & Moreira, Charles F. (2004, March 9). "Malaysian cyberlaws need to keep up." Star InTech, p.2

Khalid, H. Amir & Moreira, Charles F. (2004, March 9). "New cyberlaws may be delayed." Star InTech, p.3

Khalid, H. Amir & Moreira, Charles F. (2004, March 9). "Cybercrime: Business and the law on different pages." Star InTech, p.4

Khalid, H. Amir & Moreira, Charles F. (2004, March 9). "IT-illiteracy and lawyers: Blame the Bar." Star InTech, p.4

Lee, Mei Pheng. (2001). General Principles of Malaysian Law. (4th Edition). Shah Alam, Selangor: Penerbit Fajar Bakti

Moreira, Charles F. (2004, March 4). "Get on with IT, lawyers urged." Star InTech, p.4, c.4

Ramachandran, Sonia. (2008, August 31). "The Net is not in a legal vacuum." New Sunday Times, p.18

Rising cybercrime rate in Malaysia. (2004, October 21). Star InTech, p.2, c.3

Sharif, Raslan. (2004, April 22). "Vandals giving government websites grief." Star InTech, p.3

Sullivan, Laura. (2004, March 2). "Phishing takes centrestage." Star InTech, p.24

Surin, A. J. (2003, April 22). "Harmonising cyberlaws in a borderless world." Star InTech, p.27-29

Surin, A. J. (2003, September 4). "Data protection and privacy." Star InTech, p.16-18

Surin, A. J. (2003, October 7). "To catch a cybercriminal." Star InTech, p.29-31

Surin, A. J. (2003, November 11). "Multilateral efforts to combat cybercrime." Star InTech, p.20-22

Surin, A. J. (2003, December 9). "The power to effect ICT change." Star InTech, p.20

Surin, A. J. (2004, January 6). "Act gives MCMC wide powers." Star InTech, p.19-21

Surin, A. J. (2006). Cyberlaw and its Implications. Petaling Jaya, Selangor: Pelanduk Publications

Warren, Peter & Streeter, Michael. (2005, April 19). "Cybercrime gaining momentum." Star InTech, p.23

3 comments:

Chen Ming-fa: Data breach notices have a scalability problem. As the number of notices soars in the US, we need to better define what is a serious breach and what is not. Otherwise, the public drowns in breach notices, many of which are insignificant. --Ben http://hack-igations.blogspot.com/2007/12/does-lost-tape-equate-to-lost-data.html

Agreed. Identifying and categorizing the breaches enables executing an efficient action and priority to act against those serious breaches.

Very well-written and well-construct. Easy to understood by everyone, even though person without basic knowledge about law.

Thank you Mr Author, it really helped me!

Post a Comment